It’s been 100 years since Roy Carpenter purchased the large parcel of land that stretches south towards the sandy shores of Matunuck, Rhode Island. His brother, Kurt, raised dairy cows there for a few decades. The family was eventually approached by day trippers asking for permission to use the beach. Bud, Roy’s son, developed a parking area for them and soon sunbathers and fisherman were granted the right to camp on the land. Paths were cut through the field grass, small sites for tents were cleared and a camp store was erected steps from the ocean. The Hurricane of 1938 leveled the shop and covered the fields with sand. Nevertheless, the campers returned and their sites evolved into platform tents, airstream trailers, collapsible houses and eventually, permanent cottages.

And thus, a community was formed.

Decades ago, life at Roy Carpenter’s Beach was rustic. Springtime preparations were a family affair. Water pumps had to be primed, debris from winter storms cleaned up, and all the stuff – the pots, pans, sheets and furniture – had to be taken out of storage. Most families spent the winters in “the city” – towns in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts. The springtime migration south was a short drive for most. Still, families would often arrive in June and not leave until Labor Day. The tiny 300-400 square foot cottages might hold upwards of 14 people, sleeping on US Navy surplus bunk beds with wool Navy blankets to keep warm. Communal toilets were located throughout the camp and required walking through the rows of homes. It would take twice as long to get to them on a summer morning – it would be rude, after all, to not say hello to the neighbors.

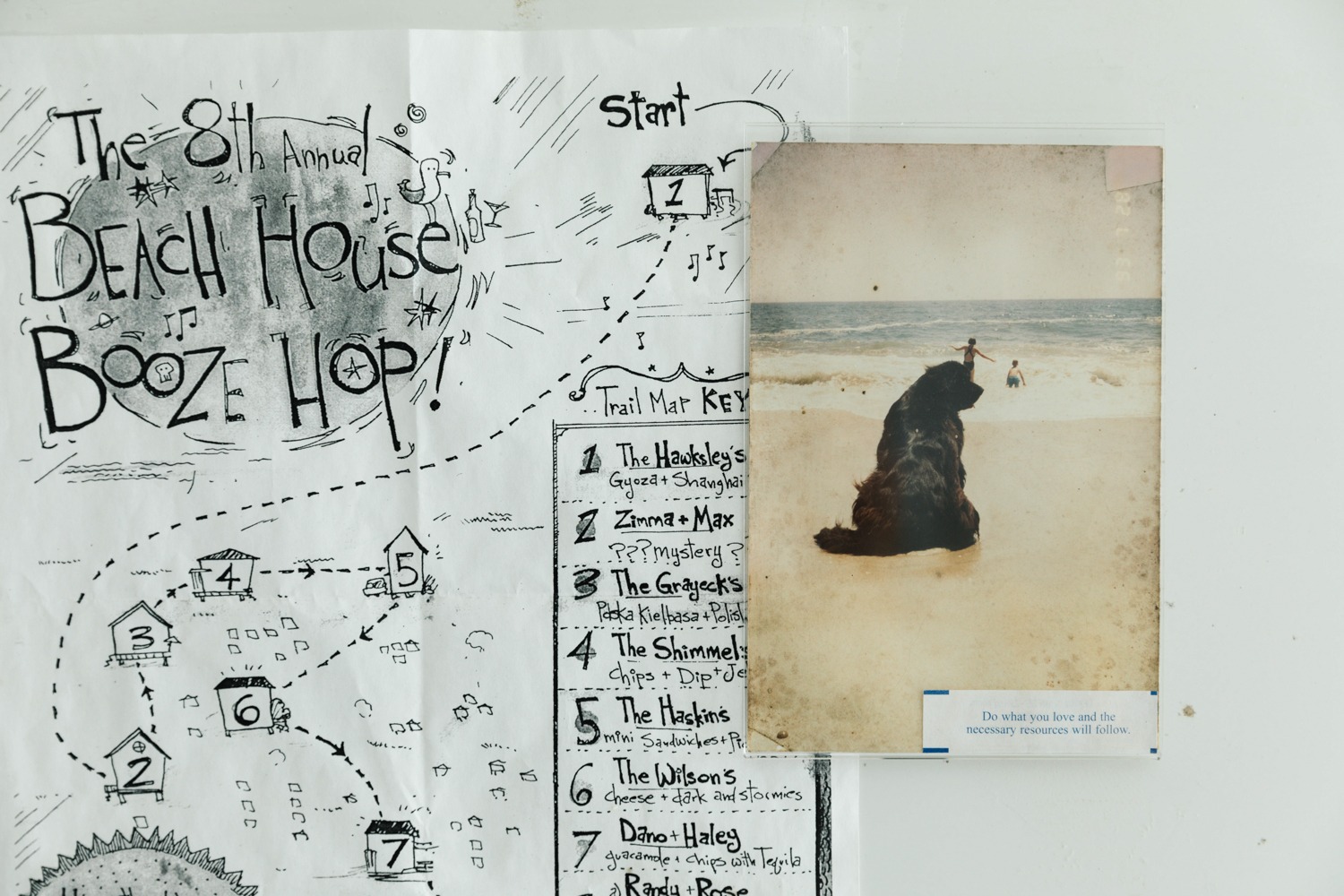

It was a simple time. Days on the beach, evenings on the porch. Children roamed, unattended, making mistakes and learning from those mistakes. Time moved slowly and the wind and the waves lulled everyone to sleep.

Today, the homes remain. Most of the porches have been turned into living rooms, adding a few hundred square feet. New families continue to buy up the small cottages and renovate them. As the land value has increased, so too has the yearly fee to live on the land. The Carpenter’s still own the property and don’t plan on selling. They’ve set up a good business for themselves maintaining the community and collecting rent.

Some of the families that helped create the community can no longer afford to live there. Many have started moving in from nice towns, expensive towns, towns with country clubs and private schools farther away. And Matunuck ain’t that sorta town. New families do their best. They try to make their cottage airtight. They want gates. Kids roam but it’s a bit more controlled now. The sandy beach is being eroded, revealing centuries’ old rocks, which doesn’t make the newcomers very happy.

They came for the sand, dammit. They brought their beach toys.

Still, the ocean doesn’t care. It continues to creep inland. After Hurricane Sandy, two rows of houses had to be moved. Two more will be moved soon. The people at Roy Carpenter’s Beach know that their community may not be around forever. But that doesn’t matter right now. It’s May. It’s time to take the plywood off the windows and dust winter’s cobwebs away.

The Sleeping Home is an ongoing photographic project by Read McKendree that studies homes and communities in New England that are active only in the summer season. They are relics from a simpler time. Both the structures and the life they represent are quickly disappearing through redevelopment, renovations and changing social structures.