As we walked around the grounds of the Thomas Mann House in the Pacific Palisades, Benno Herz, Program Director and Head of Fellowship Programs, explained why the German government was interested in acquiring the property and developing programs:

Even as Benno framed the House’s mission, it was hard not to be distracted by the elevated landscaping–a hilltop with soaring palms–and the broad horizontal repose of the mid-century modern architecture, albeit subdued with lingering tones of the International Style. But here was a house with a big story–for any house, let alone one that stands inconspicuously in this toney suburban neighborhood to the west of Los Angeles. The house, designed by J. R. Davidson, who was born in Berlin and emigrated to Los Angeles in 1923, is certainly interesting architecturally, but not a superstar. It is a beautiful house…but it was an extraordinary home.

Thomas Mann, the esteemed German literary giant, was himself a superstar and Nobel laureate. Together with his wife Katia Mann, they built and moved into this house in 1942, often visited by their oldest daughter Erika Mann, who was a writer, actress, journalist and outspoken critic of the Nazis herself and often inspired and informed her father’s political activities. Thomas Mann had for years been speaking out against the Nazi regime and German anti-Semitism; consequently, he and Katia had been in exile since 1933 (his German citizenship was revoked in 1936) and eventually settled in Los Angeles, first renting a house in Brentwood in 1940. Mann and his family were part of a humanitarian network that aided persecuted people and refugees from a dangerous and devastated Europe, and they were also part of an intellectual community that critiqued both totalitarianism abroad and America’s capitalist excesses. They found and founded an émigré community of intellectuals (many also exiled from Germany) already here and still expanding.

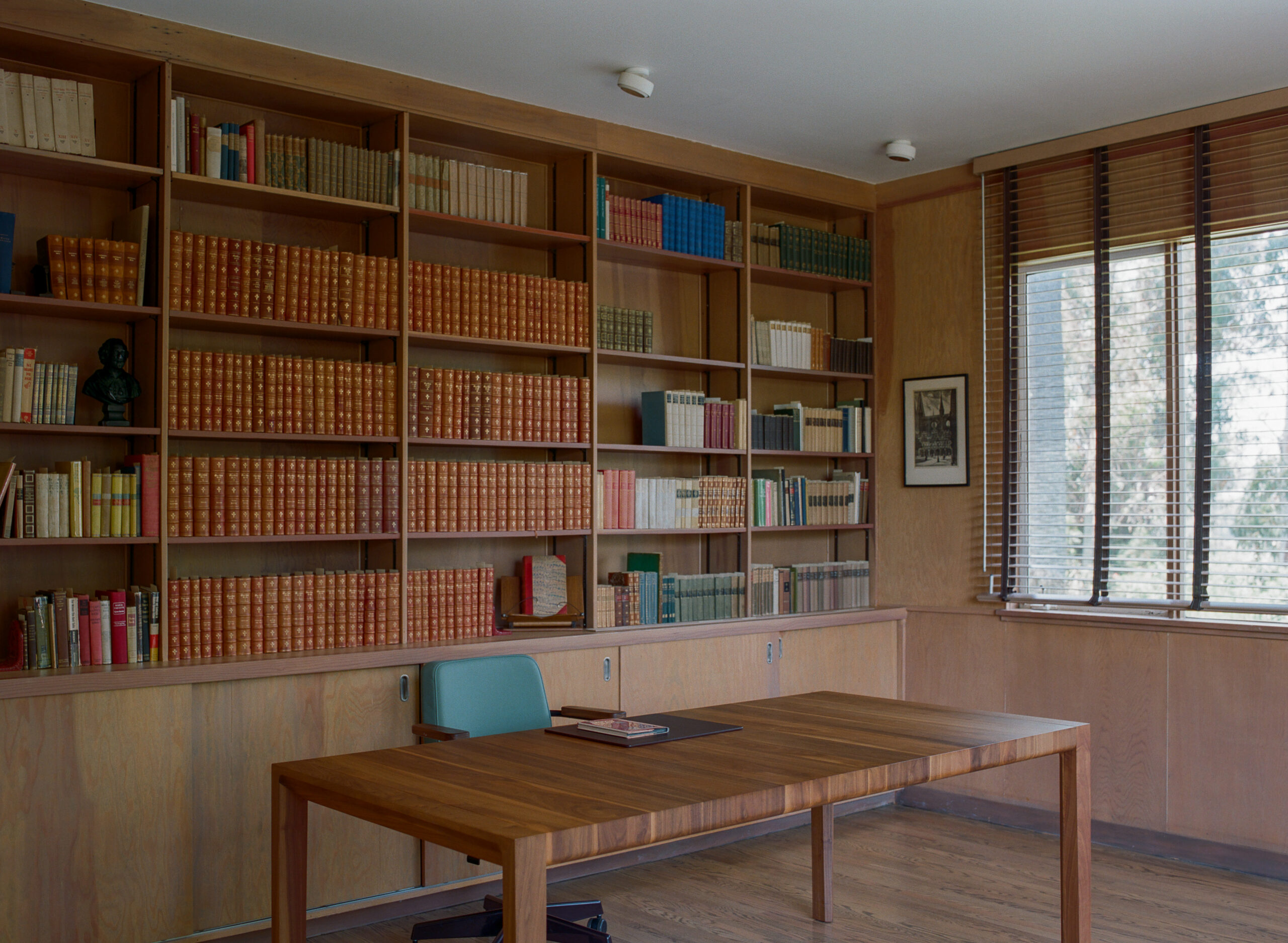

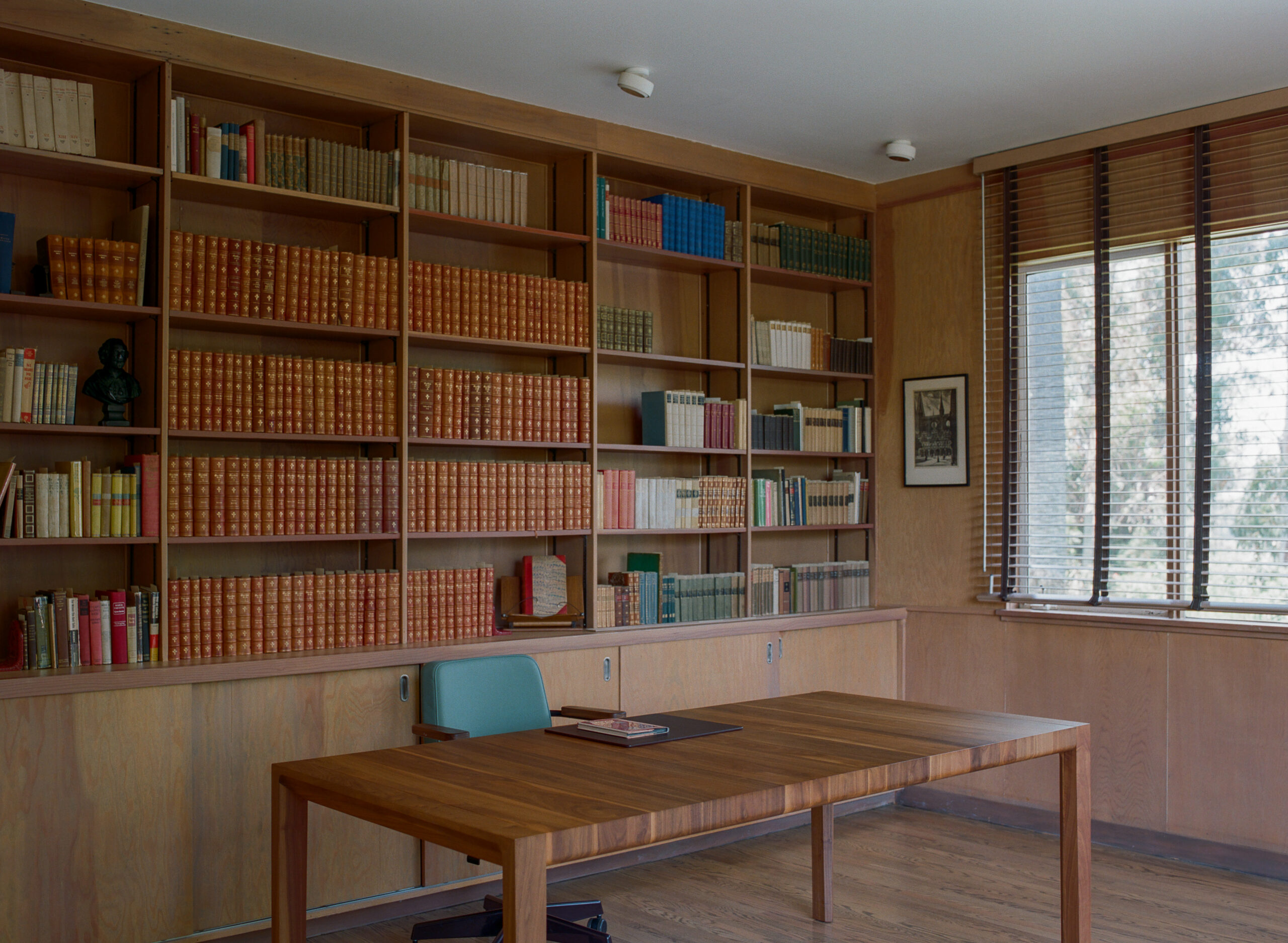

Benno and I walk past the pool (added after 1952, by the next owners of the house) and turn the corner around Mann’s study towards an enormous date palm—incidentally also thriving transplants to southern California. Seen from here, the study angles away from the main part of the house; it stabilizes less the footprint of the plan than it animates a reach. This axis, which one even experiences subtly while walking through the shifted hallway and within the study itself, is affecting emotionally—as a gesture of aspiration and yearning, as well as of distancing (from the household), a constructed seclusion that bends toward other communities. It does not look back at the domestic part of the house; it does not enfold or protect an intimate courtyard. It is connected to home, but also on its own, a kind of gently tethered landing module. It looks slightly away from the house proper, glancing over its shoulder, so to speak, activating a kind of dual vision, even while providing ballast for the whole project of living in exile. As Erika wrote, “We are at home wherever the desk stands”. (Wefing, p.89)

In Building Paradise: Exile Architecture in California (Villa Aurora Architecture Symposium 2003), art/architecture historian Heinrich Wefing illustrates the entanglement of exile and the design of living-space by describing the choices of the Mann family at “Seven Palms”, as they named their home. Here they (somewhat reluctantly) leaned into the architectural modernisms of southern California but surrounded (or comforted) themselves with traditional German furnishings. These joined dissonant conditions, Wefing writes,

Perhaps even more important in that re-creation of “lost” home were the dynamic friendships and interactions of the exile community. These are the subject of what Benno calls his “covid project”: Thomas Mann’s Los Angeles: Stories from Exile 1940-1952 (Angel City Press 2022), co-edited with Nikolai Blaumer, the previous program director. Renovations of the house, which was purchased by the Federal Republic of Germany in 2016, had just been completed and the residency program had just started in 2018, when the pandemic closed everything down. So, Benno and Nikolai pivoted, gathering and soliciting stories they had already been hearing about the exile community, and publishing them: first on social media channels, next as a Digital Humanities class with University of California Los Angeles, and eventually in printed book form. It is a page-turning collection of stories by significant scholars and authors on the people (artists, writers, “Hollywoodites”, politicians, intellectuals) and places (airports, diners, concert halls and theaters, churches and temples, beaches, highways, universities) that encompassed the southern California world of the Mann family—all anchored by a close-knit group of (illustrious) dear friends, many of whom lived close-by and gathered frequently in each other’s homes. Through evenings of food, music and conversation, these exiles and emigres reciprocally performed their own conditions of care—a gesture which continues today through the Thomas Mann House Fellowship residency program.

Although Benno’s and my conversation was both stimulating and leisurely, the tour was actually quite short, restricted to the “public” rooms—because above us on the second floor, residents were working, writing, resting, engaged in conversation, considering issues, imagining possibilities. The Thomas Mann House residency provides for the non-interrupted depth of sustained thought that is so hard to find in our present world. Everything here is not for display, for observation, for immediate consumption, or posing for quick response. Administered by the U.S. non-profit organization “Friends of Villa Aurora and Thomas Mann House”, the house is still protectively a “family” home, not open to the public, nourishing the growth and engagement of ideas, in an intimate and safe setting. Occasional private events at the house, such as the current series of interviews/workshops addressing Democracy and Vulnerability (2024) host further exchange and are often later shared on the internet. Off-site co-sponsored programs or conferences, such as Moral Code – Ethics in the Digital Age (with UCLA, 2019), reach further and more publicly to debate current issues. All in order to meet the world.