From a first floor window of the Palazzo Monti, a brilliant gold square appears out of nowhere, as though suspended from the blue Brescia sky.

Edoardo Monti is helping artist Paolo Incarnato install his latest work – a series of frames custom made to cover the windows of the palazzo. Across each frame are stretched gold foil sheets – insulation blankets distributed to refugees when they arrive on Europe’s shores after making the perilous crossing from Turkey and North Africa.

Edoardo leans out the window laughing, shouting up to Paolo, who manoeuvres the frame from a window above. From outside, the gold sheets gleam in the late afternoon sun, their brilliance in striking contrast to the pale ochre of the building’s 800-year-old facade.

The Palazzo Monti sits at the heart of Brescia’s historic centre. A short train ride from Milan, the city is elegant, sombre and, unlike neighbouring Verona, pleasingly devoid of tourists. Following an industrial boom in the1980s the city expanded to form an urban industrial sprawl stretching north to the Garda mountains. But the centre, dotted with Roman ruins, medieval cloisters and imposing piazzas, remains untouched.

On this languid afternoon, the sun gently illuminating the walls of the downstairs studio, Palazzo Monti feels a long way from New York, where Edoardo was until last April working full time in a PR role for Stella McCartney. Just 25 when he launched the residency in 2017, Edoardo managed the palazzo remotely, before moving to Brescia full time.

In the 1940’s, Edoardo’s grandfather bought the building, converting the ground and first floors into lawyers’ offices. He and Edoardo’s mother lived on the floor above. From the 1980s, the palazzo was rented out as apartments until 2016, when Edoardo reclaimed it to found the residency. How does his family feel about the building’s most recent incarnation? “They love it,” says Edoardo, “They were a bit sceptical at the beginning because I honestly had no idea how to make it profitable.”

But success has come. With regular exhibitions showcasing residents’ work, the palazzo, now a registered cultural institution, has seen much of its production sold to local and international collectors, with a sell-out show in December.

The 27-year-old runs the residency single-handedly and with seemingly boundless energy; cooking, cleaning, ferrying artists to and from the train station, fetching them materials and organising events and exhibitions. “It’s been important for me to come back, to leave what I had in New York for 5 years,” he tells me earnestly. “Because now I can build relationships, create those human connections with people who will then invest in the project.”

It’s clear on entering the palazzo that the space comes alive, and changes form, along with its residents. At any given time, up to eight artists from around the world are working, cooking together in the pantry kitchen or eating and drinking at the long table that Edoardo regularly rolls out for candle-lit dinners. The artists remain for up to two months, and each leaves their mark in the form of one work, left as a donation to the palazzo in exchange for their stay.

Edoardo compares this approach, and his approach to art collection, to the model established by the Medici family in Florence in the 15th century. “You would call Michelangelo, who was broke, and you would say ‘I’m going to buy all your production, invest in you,’” he explains as we wander Brescia’s streets, passing yet another breathtaking church. “Go out, create, have fun – that’s pretty much the concept they invented. Patronage.”

After buying his first ever artwork at the age of 14, Edoardo likens his passion for collecting to a disease, or addiction. He laughs with embarrassment at his first purchase; a pop-art painting of Mona Lisa, “on the phone or something.” How did it feel? “It feels amazing because you own it, it’s yours,” he enthuses.

Davide, a young Italian sculptor based in Copenhagen, is occupying one end of the ground floor studio. In the hush of the early hours, he hand-mixes cement in the palazzo courtyard, preparing a final layer for his latest sculpture. He throws the mixture, made of powdered marble from local quarries, to form textured mounds at the base of a mirror.

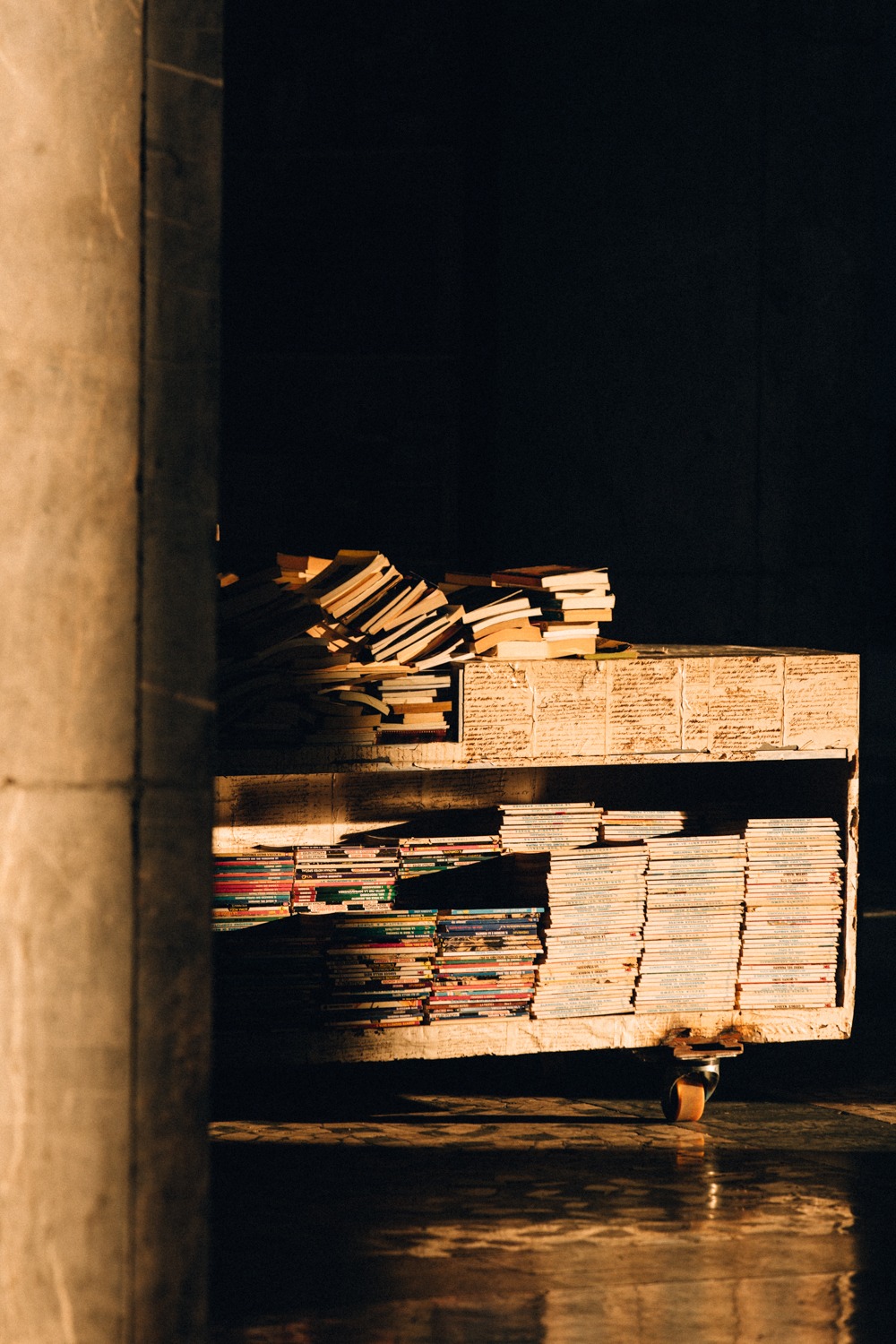

“Edoardo doesn’t push you at all,” he tells me of his host. “You can just explore. There is no pressure.” The sculptor’s donation is a three-tier bookshelf for one of the first floor exhibition spaces, its shelves great slabs of local marble. Like many of the artists here, he was inspired by his surroundings, but also by practicality. “This just happened because Edoardo had ordered a lot of books,” Davide laughs. “He was piling them in the kitchen, so I said, let’s make a bookshelf.”

The high ceilings lined with wooden beams and stripped walls form an almost monastic backdrop for the artwork placed haphazardly around the room. Above a grand piano, a portrait of Edoardo by Australian artist Loribelle Spirovski stares out, its soft strokes blurred and abstracted but for one eagle-sharp eye.

This is one of multiple works that depict the collector, the most notable of which greets visitors as they arrive at the palazzo. At the top of the sweeping stone steps in the ornate entrance hall of frescoes painted in pale pinks, blues and sage, lies a full-body replica of Edoardo. A prototype for the final aged bronze sculpture, the figure lies naked on its stomach beneath the tall window, its head resting on its arms.

A few weeks later, the real Edoardo is striding along London’s Strand, coat billowing, taking a break to meet me during his frenetic schedule of studio visits. I show him the Instagram of a painter friend and within minutes he’s scheduling a meeting. “I’ll get her to the Palazzo,” he grins, carried away as ever by the beauty of a detail, a certain colour pallet. We say goodbye and Edoardo sets off again to fill his Palazzo with artists, just as they fill his palazzo with Edoardos.