Jean Prouvé

Avant tout J'ai été un industriel

“I am just a worker,” said Jean Prouvé. “And that’s how I started […].” During the First World War – when he was a teenager – he apprenticed under a master blacksmith.

That was the starting point of his career. Although his first pieces were small decorative objects, he gradually made bigger things, eventually making gates, railings and balconies – all for local clients in the city of Nancy. In 1931, he steered his company, Ateliers Jean Prouvé, towards mass industrialisation. By the mid-1930s, his involvement in the construction process had extended from the design and construction of elements and encompassed the entire structure. For Prouvé, architecture and design were tools of transformation at the service of the community.

All his work was geared towards a single goal: mass production and the industrialisation of construction so that his designs could reach as many people as possible. Progress was a desirable ideal that would improve social life and overcome inequalities. Prouvé experimented and innovated so that others could benefit from his contributions and incorporate them into their projects, thus turning his ideas into collective responses to shared problems.

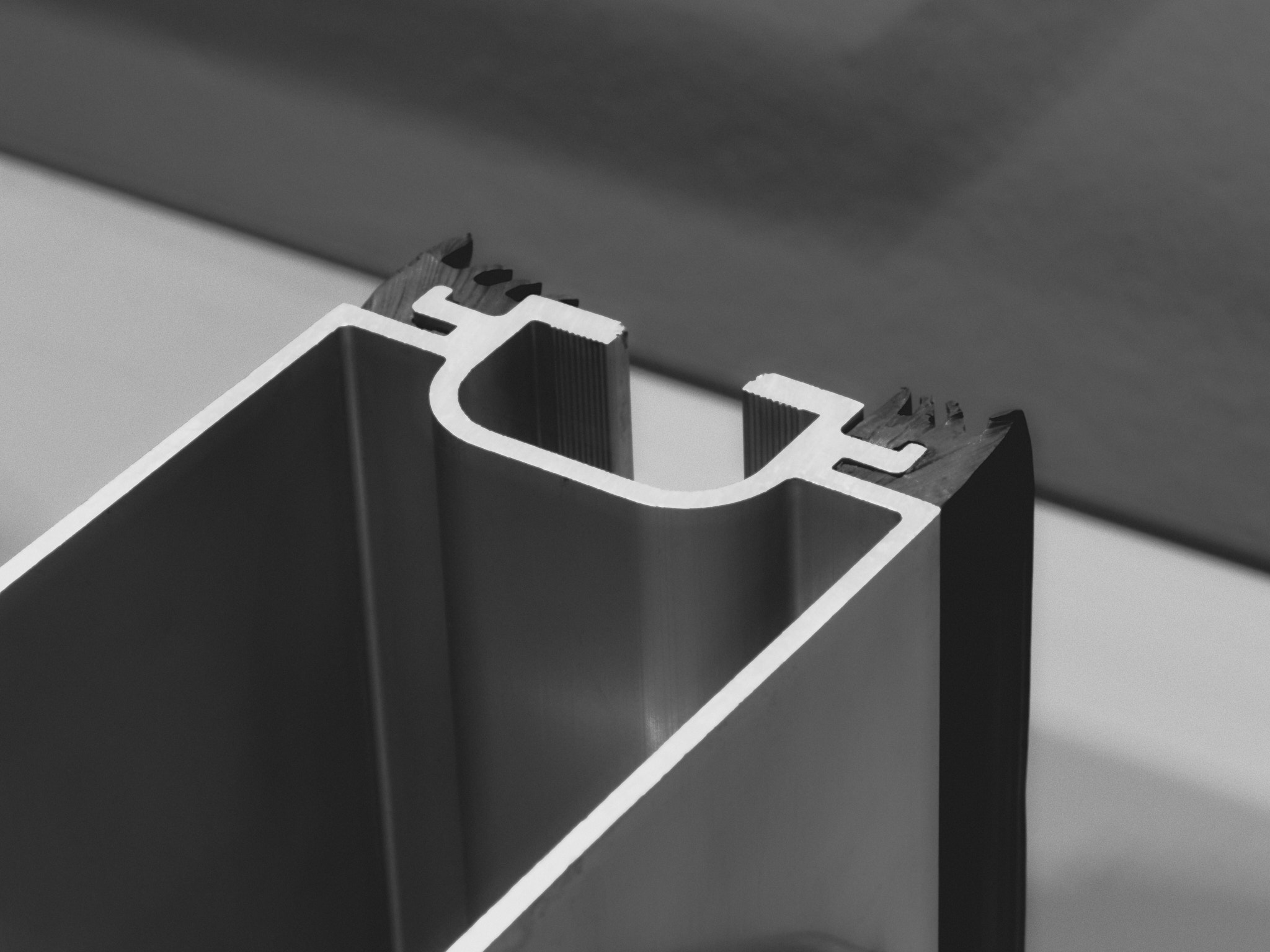

“Between 1934 and 1935 I came up with another way of making architecture; in other words, another way of using materials […]. I imagined buildings having a structure – just as a human being has a skeleton – to which complements are added; and the logical complement to a skeleton, whether steel, concrete or wood, was to wrap it in a façade, one that was light because the structure is self-supporting.”

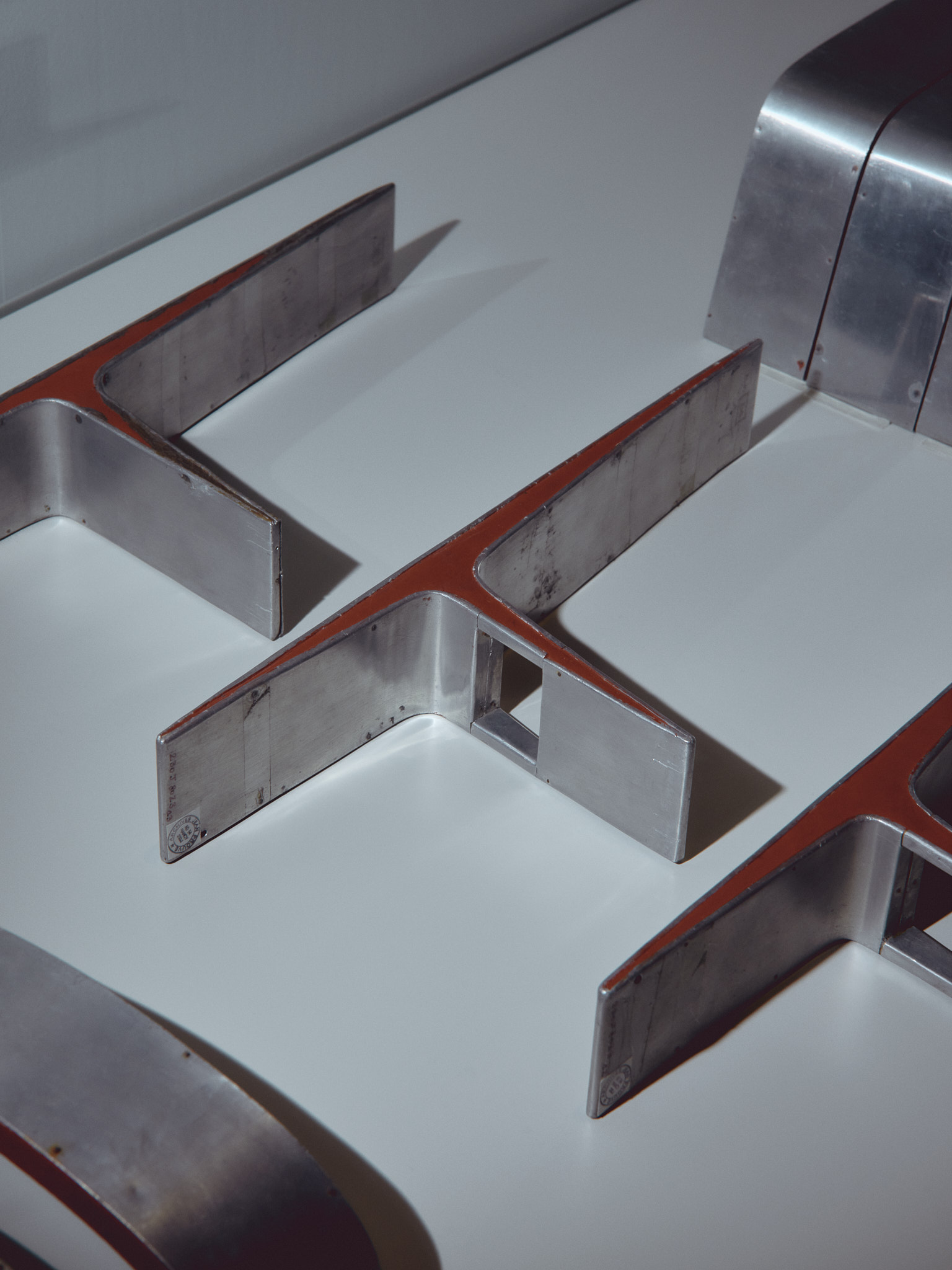

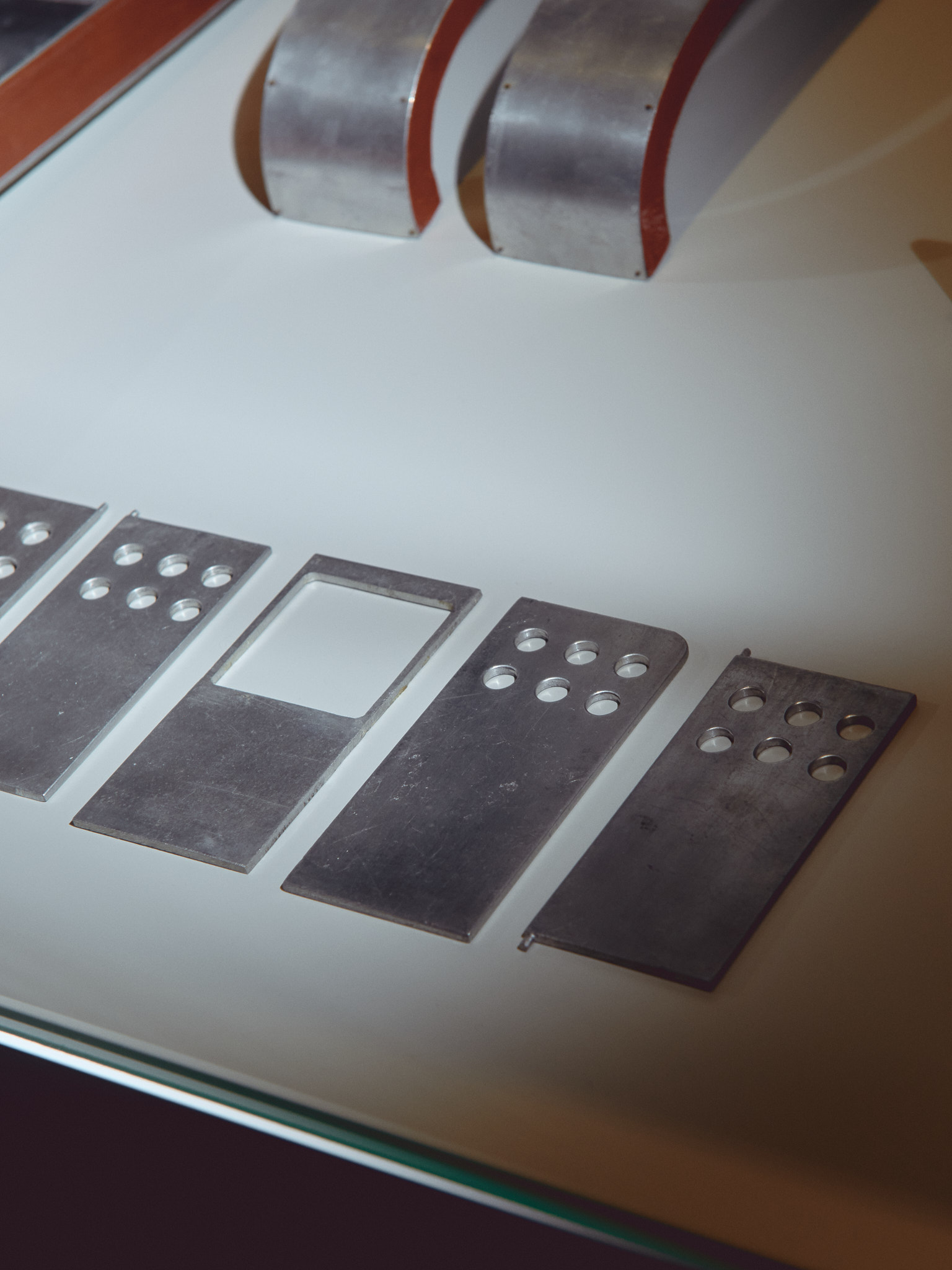

When it came to furniture, Jean Prouvé’s great contribution was to create very durable furniture that was often foldable and reclinable, using a very limited number of materials. From a technical standpoint, folded sheet metal gave strength to the object, distributing the weight equally on all the legs of the piece of furniture.

One of his most successful models was the 1934 Standard Chair: perfecting it over time, he created various adaptations for fifteen years until, in 1950, it became a classic and was renamed the Cafeteria Chair. The silhouette acquired its definitive line once the shape had been defined and tested, regardless of the material from which it was made. “To my mind, a chair has to be light. Chairs always break at the point where the back legs are joined to the seat. That’s why all my furniture uses forms of equal resistance.”

With the idea of creating products for the people – and with faith that progress would benefit society – Prouvé designed quality accommodation and furniture for collective facilities, always ensuring his work had an avant-garde look to it. “We need prefabricated houses,” he asserted in 1946. From that moment on, he worked from his factory in Maxéville, mass producing pieces in sections that could then be assembled on site. He built the Tropique House (1949) using this method. It was a Standard House with a central portico but with two particular characteristics: it was light – the number of aluminium elements was optimised – and it had a natural ventilation system thanks to a double ventilated roof.

With the Métropole House, built in 1950 as a variation on the Standard House, Prouvé once again used the structure of a central portico of folded and assembled sheet steel to which he added a roof and façade panels. One of the highlights and innovations of this house was a glassed-in winter garden. For the 1951 Maison Coque, Prouvé created vaulting that was continuous, self-supporting and light. Put together using curved roof panels and metal supports, the structure could be assembled in just 48 hours as demonstrated at the 13th Exhibition on Social Housing in Paris.

Fonds photographique Jean Prouvé, ingénieur et constructeur (1901-1984)

Fonds photographique Jean Prouvé, ingénieur et constructeur (1901-1984)Prouvé designed the exterior of the houses as well as specific furniture for the inside. It was a way of working that turned him into a creator of both architecture and furniture, and the models for the projects arose according to each particular commission and the specific uses required. His versatility to adapt to different functions and to improve pieces over time can be clearly appreciated with his Kangourou armchair (1948).

A sort of lounger with a sloping backrest, it had a tubular steel frame and wooden elements joined to the seat and backrest. “Constructing a piece of furniture is a serious thing. The problems that need to be solved are as complex as those of large buildings. I would compare them to those involved in the manufacture of heavy-duty machines, and that leads me to construct them with the same interest, with the same rules regarding the durability of materials, and even with the same materials.”

‘The Universe of Jean Prouvé’, an exhibition organised by CaixaForum in collaboration with the Centre Georges Pompidou, showcases the career of Jean Prouvé and highlights his architecture for public housing, as well as the extraordinary originality of his work as a furniture designer who was guided by simplicity, elegance and austerity.