Fondazione Prada

A stairway to contemporary art

Fondazione Prada is an icon of the city, a pilgrimage site for enthusiasts and professionals alike in the world of art and architecture.

Founded in 1993 and presided over by Miuccia Prada and Patrizio Bertelli, the foundation opened its headquarters in Milan to the public in 2015. It is located in Largo Isarco, in the Vigentino district at the edge of the city centre, not far from the Piazzale Lodi stop on the yellow metro line. After seven years, the district already bears the fruits of the boost the foundation has given to its regeneration, and also to culture in general, as Fondazione ICA, Institute for Contemporary Arts, has also found a home a short distance away.

Fondazione Prada has its home in an early twentieth-century distillery transformed by Rem Koolhaas’s OMA firm into a centre for contemporary art. With a surface area of almost twenty thousand square metres, it combines existing buildings and three new constructions (named Podium, Cinema and Torre) into an articulated architectural campus that brings together several exhibition spaces, a cinema, a bar and a library, and is interspersed with open-air areas where visitors may relax.

Envisioned “as an outpost to analyse present times through the staging of contemporary art exhibitions as well as architecture, cinema and philosophy projects”, the foundation hosts both temporary and permanent projects. It is designed as a place in which to spend hours, a place that, despite the rationality of its architecture, is welcoming and invites you to stay, to linger. And that is a bonus for the Milanese, who no longer have to go to Beacon to see a Walter De Maria, or to Los Angeles to see a Jeff Koons.

With Germano Celant as Artistic and Scientific Superintendent (until his death in 2020), a dynamic schedule of exhibitions, special projects, film festivals and meetings have, over the years, stood out for their high quality: the inaugural exhibition on copying in classical art, co-curated by Salvatore Settis and Anna Anguissola; the solo shows of Domenico Gnoli, Goshka Macuga and Francesco Vezzoli; “The Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures”, conceived by Wes Anderson and Juman Malouf.

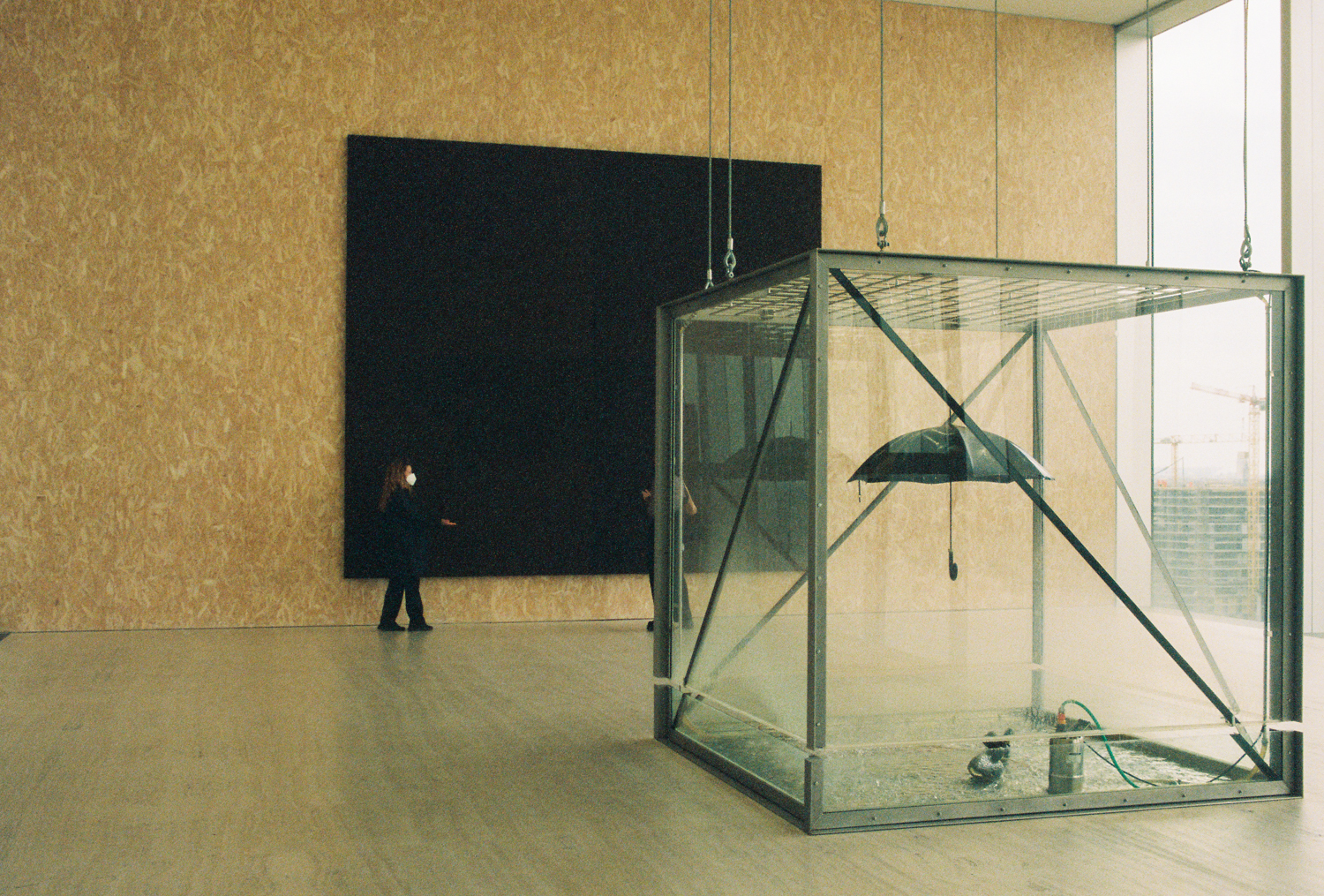

Additionally, the spaces of Fondazione Prada are home to a number of permanent installations. The Haunted House is a gilded building that houses both Robert Gober’s installations and works by Louise Bourgeois that evoke atmospheres and explore themes based on the body, childhood and sexuality. At a different architectural scale, Torre is a 60-metre-high white concrete tower that opened in 2018, and provides an even more articulated path. It was designed as an ascent into a space as vast as it is intimate, aspects apparently in antithesis but formally expressed and conveyed in the choices of the installations.

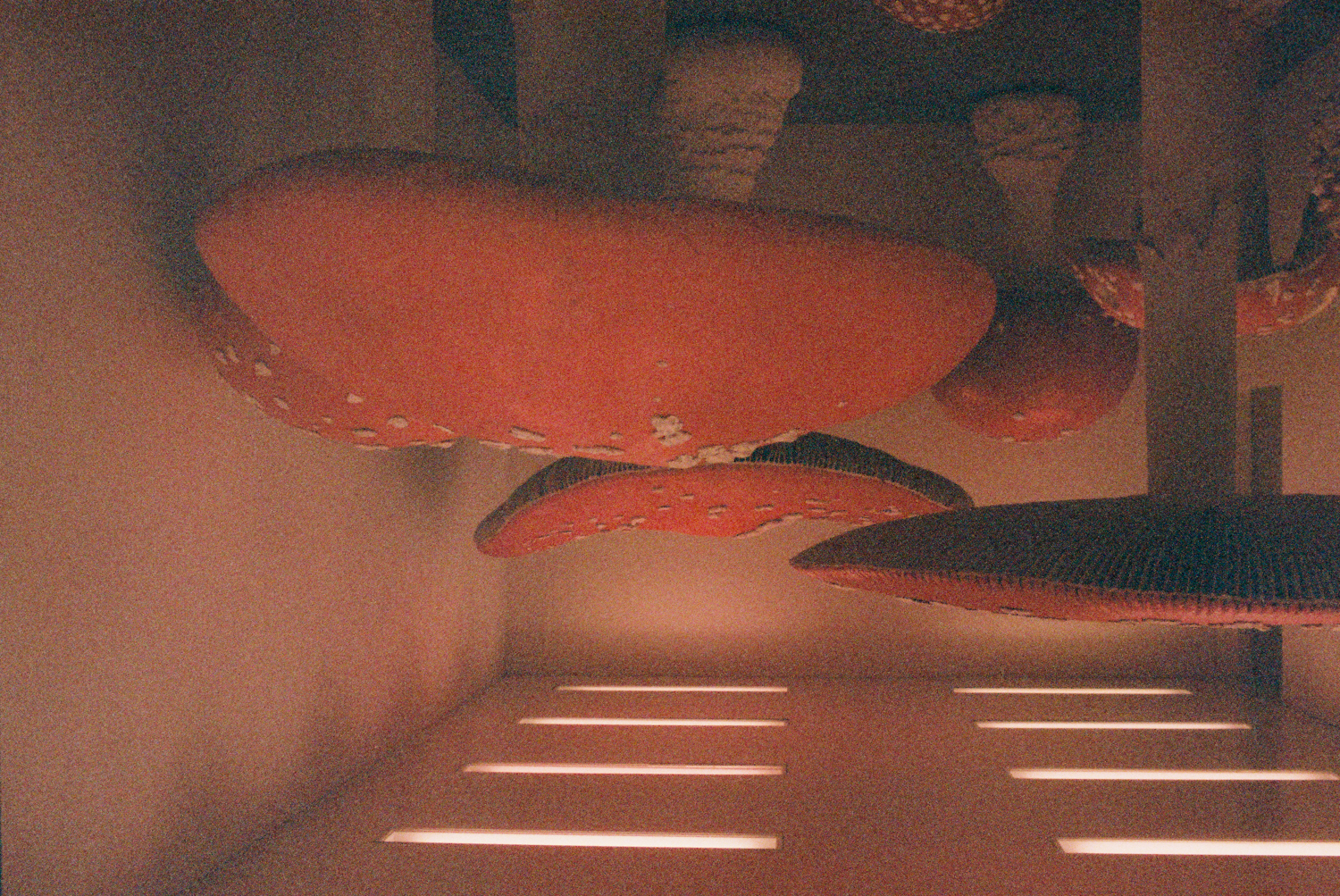

It was the dialogue between the curator, Germano Celant, and Miuccia Prada that resulted in the “Atlas” project, installed within it and bringing together artworks in “solos and confrontations, created through assonances or contrasts”. Examples of this include a room that exhibits a series of works on sicofoil by Carla Accardi created between the mid-1960s and mid-1970s in confrontation with the painted steel Tulips, by Koons; Michael Heizer’s geometric paintings and sculptures that are visually woven into Pino Pascali’s Confluenze (1967), in aluminium, water and methylene blue; Carsten Holler’s series of rotating mushrooms in Upside Down Mushroom Room, 2000, which competes for dominance on Instagram with the video projection of Blue Line, by John Baldessari.

The title of the exhibition refers to the idea of a “possible mapping of the ideas and visions of the artists that have contributed to the activities of the foundation over the years”. Continuing on with the tour, one can admire Battaglia, a polychrome ceramic frieze with fluorescent paint created by Lucio Fontana in 1948 for the Cinema Arlecchino in Milan now visible in the foyer of Cinema, while an underground space is home to Thomas Demand’s permanent installation Processo Grottesco (2006–2007), which brings together the cardboard model of the Caves of Drach, on the island of Majorca, comprising almost a thousand sections, and the visual material that served as an iconographic source for the creation of the photograph Grotto – a work that creates “a short-circuit between reconstructed form and real vision, and uses the impersonal instrument of the camera to provide a personal interpretation of the image”.

And then there is the magical Bar Luce, which was designed by the American director Wes Anderson in the style of a typical Milanese café of the mid-twentieth century, inspired by the screenplays of such films such as Vittorio De Sica’s Miracolo a Milano (Miracle in Milan), from 1951, and Luchino Visconti’s Rocco e i suoi fratelli (Rocco and His Brothers), from 1960. Between the pastel tones of the seats that recall the themes of these films and the wallpaper that reproduces the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in miniature, Bar Luce is a place for rest and refreshment where one almost feels like the protagonist of a film with an international flavour.

One can easily imagine being secretly filmed by a camera while reflecting on the immensity of what art can unleash and the echoes that are amplified in these spaces. The hope is that the experience at Fondazione Prada will not end with an Instagram post, but that it will result in an awareness, namely – to paraphrase Friedrich Nietzsche – that we still need and will always need lies in order not to die of the truth.