The Jerwood Gridshell building is a wooden geodetic structure designed by Edward Cullinan Studio and Buro Happold, nominated for the Stirling Prize in 2002.

Located at the Weald & Downland Living Museum, an independent museum that conserves historic buildings and documents stories of rural life in the area, the building is used as a conservation workshop and storage space for the museum’s extensive artefact collection. Julian Bell, who has worked as a Curator at the space for nearly twenty years tells us more about this celebrated building, how it enables his job and what we can learn from buildings and artefacts of the past.

What is your role at the Weald and Downland and specifically the Gridshell?

As Curator I have responsibility for the care, research, interpretation, growth and access to the nationally important buildings and artefact collections and improvements in access to them.

These designated collections include some 53 historic buildings rescued from destruction and re-erected on the museum site, together with some 16,000 artefacts covering building parts, trade tools, agricultural implements and rural trades and crafts; ranging from bricks and horseshoes to wagons and agricultural machinery.

I am responsible for the care and expansion of the buildings collection including the dismantling of new acquisitions and re-erection of existing examples from the store. I also have responsibility for the development and implementation of temporary exhibitions, of which we try to run between 4 and 6 each year, as well as administering a team of dedicated volunteers and promote the museum at a range of external events.

What do you like most about the Gridshell?

A number of things. The construction technique of the upper area is fantastic and extremely clever and the space it forms continues to be pretty breathtaking. I like the fact that although it’s a modern construction, it’s still a timber framed building at heart and therefore sits comfortably with our other exhibits. The initial driving force behind the construction of the Gridshell was to provide a store for the museum’s artefact collections. To have a purpose-built store, newly fitted out, ready to be filled with artefacts is something that very few collection managers or curators ever have the chance to work with.

What in particular do you like about the architectural design of the building?

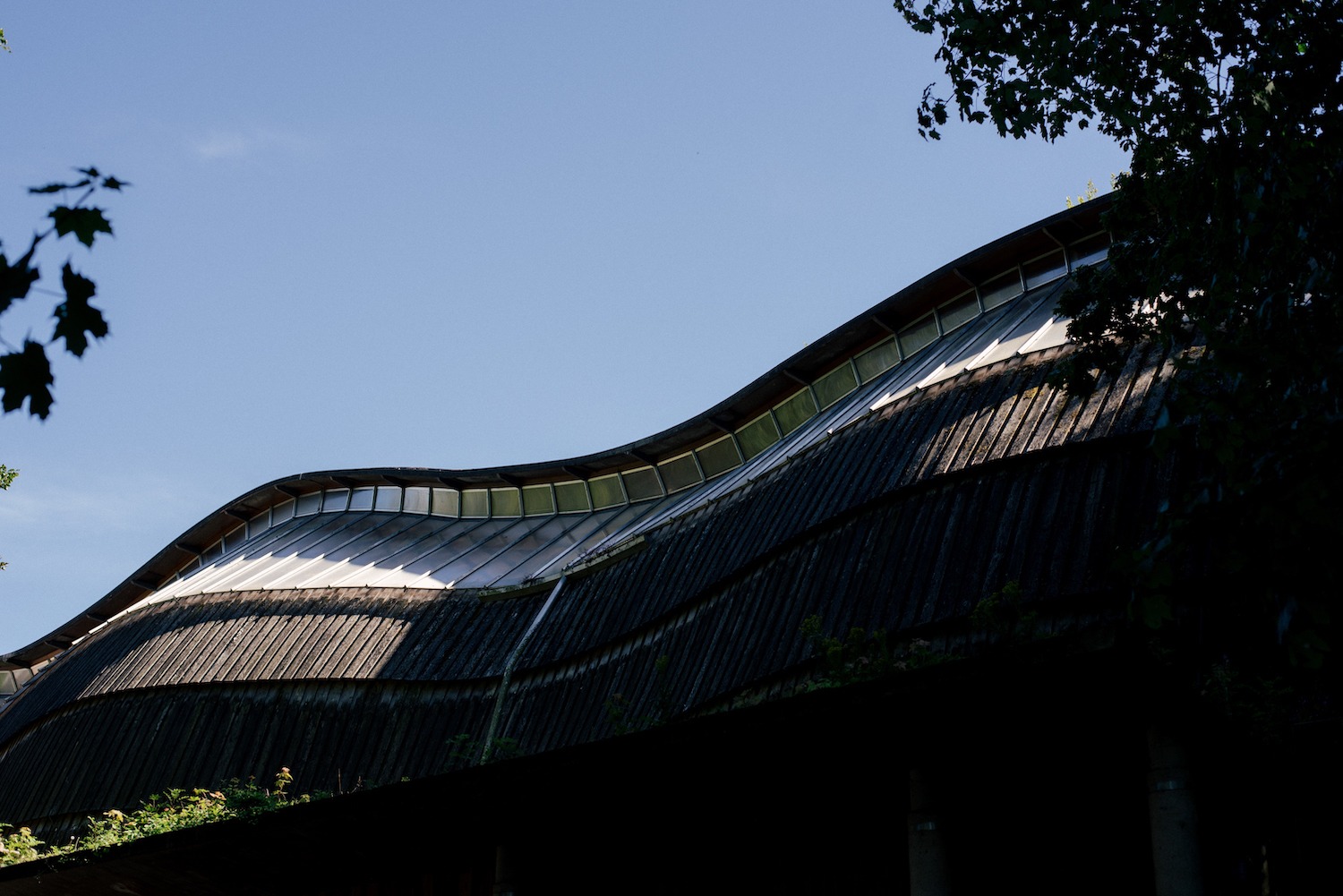

I particularly like the smooth, flowing contours of the upper section, designed to mirror the shape of the South Downs. And the way that all space in the upper Gridshell can be used without it simply being four walls and a roof.

The Gridshell was designed by Cullinan Studio who place great emphasis on the importance of nature and ‘restoring the connection between people and nature’. How much does the environment around you, the woodland, and the museum, affect your experience of the space? Does it benefit it?

The majority of the Gridshell does sit very comfortably in the surrounding woodland and downland landscape, especially since the external cladding has weathered to blend in with the colours of the adjacent trees. Viewed externally it does for the most part look as though it ‘belongs’ in its surroundings.

I have to say that when I’m inside the building I don’t really get any feeling of connection to the surrounding landscape, partly because the Gridshell is so big. When inside one of the museum’s smaller exhibit buildings, there is a definite sense of being part and parcel of the surrounding geography. The upper area is a very pleasant and inspiring place to work, however the only time I really feel connected to the outside is when it rains, as even the sound of a light shower is magnified to a heavy downpour.

How is the building used on a day to day basis and how does its design enable this?

Before the Gridshell was built, the museum had virtually no inside workspace suitable for larger objects or buildings. We also had very limited space for meetings or courses, or anything else which required more room than the historic exhibit buildings on site could offer. The Gridshell is therefore in constant use; as an office, an artefact store and workspace, as a conservation space for dismantled buildings and larger artefacts, as a meeting/working area for conferences and courses, as a venue for weddings, birthdays and other celebrations. The individual but simple design of the structure lends itself to be appropriate for the huge variety of activities which take place in there.

In your role, you predominantly look after and restores buildings and artefacts of the past, what have you learnt from these examples? What principles are still applicable today?

Top level craftsmanship and materials will last. Not all modern materials and techniques are necessarily an improvement on those used in the past – quite often, just the reverse. A lot can be learned from dealing with historic materials and understanding how and why things were done as they were. Using hand tools rather than powered, which is predominantly how we work on items, gives a lot more insight into the nature of the material being worked on. This understanding is of equal benefit when working on modern items. Constant awareness and regular maintenance are essential if historic items (buildings and artefacts) are to survive in good order. This is exactly the same for modern examples too.

If you left your job or couldn’t visit anymore what would you miss most?

In terms of the museum as a whole I’d miss the woodland areas and one or two of the buildings in particular. The Gridshell has been such an integral part of my working life for the last 18 years that I’m sure I’m bound to miss it.