Elegance and Eclecticism

The Home of Carlo Mollino

Perched on the banks of the River Po in the city of Turin, is the perfectly preserved Casa Mollino. A treasure trove of ideas, objects, patterns and colour, the lavish apartment designed by the architect-designer-photographer, Carlo Mollino, offers an insight into the machinations of the man himself, a veritable 20th century polymath.

Technically-minded and unfailingly meticulous, Mollino’s approach, the way in which he viewed the world, led him to a career in the arts; driven by a desire to understand and unpick, each facet of his life – architecture, design, photography, aerobatics, skiing, race car driving – was an opportunity to arrive at an elegant and efficient solution, a fully comprehensive theory. Coalescing around speed and aerodynamics, engineering and artistry, Mollino’s interests reflected those of the time, a period in which Futurism and technological progress were in the ascendant.

As both an architect and product designer, Mollino was committed to modernism. In his first apartment, he installed a sophisticated kinetic light that consisted of a serpentine track that snaked across the ceiling, along which a single pendant light could be drawn, bringing illumination to wherever it was most needed. The slick, minimal shaping of the acclaimed ‘Fenis’ chair (1959) has a lightweight construction that looks simultaneously architectural and organic; and his ‘Teatro Regio’, completed at the end of his life in 1973, has a rich, cinematic quality thanks to the grandeur and precision of its composition.

Through a wrought iron gate and up an unremarkable flight of stairs, one enters into another realm: a collage of the Baroque and the Modernist, the plush and the plastic. A place of wild contradictions and myriad delights, the fully remodelled apartment was never inhabited by Mollino – though it was intended to be where he would spend his final days, had he not died at the relatively early age of 68.

At the time of its making, the term ‘eclectic’ was understood as an insult – however, in its contemporary form, the word can most certainly be applied to Mollino’s interior, which takes the best and most beautiful from a huge range of cultures, civilisations, time periods and value systems. Nestled together, there are net curtains and murano glass chandeliers, zebra skin rugs and cow-hide chaise longues, giant clam shells and Chinese Foo Dog figurines. Grand paper lanterns have glamorous black lacquer finials and long dangling tassels. There is leopard print wallpaper and rooms lined with Italian tiles in bold patterns and colourways. There are casts and busts, a giant turtle shell and exotic butterflies pinned and mounted in frames. Jean Shrimpton and Bridget Bardot hang in the bathroom, and mementos from Mollino’s life are lined up on glass shelves.

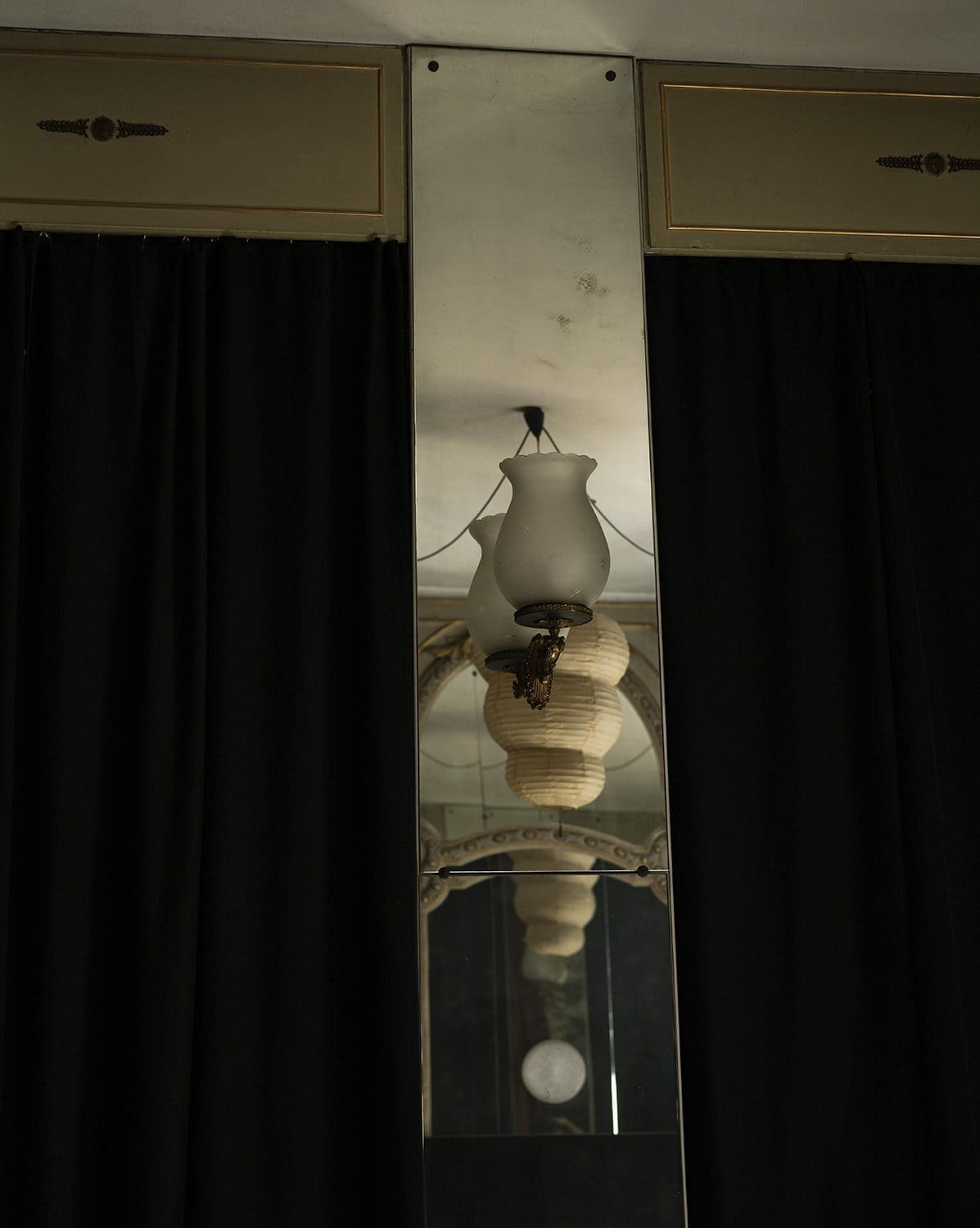

Panels line the walls, transforming the original architecture of the Villa Avondo (1888) into something unconnected to any particular era, period, style or place. Sheets of rattan, framed in black with gilt accents, create cover for the bookshelves behind; printed reproductions of an 18th Century pastoral scene, enlarged and magnified many times over, decorate the walls trimmed with traditional wooden beading and ornate rococo carvings; and panes of mirrored glass cover almost every wall of the apartment, though their reflective surfaces have dulled over time, becoming fogged and frosted, turning a milky, pale grey.

The living spaces are mostly open plan: three rooms, as tall as they are wide, that run into one another, each looking out onto the river below – however, Mollino designed the space so that it could be reconfigured in a number of different ways. Japanese-style sliding doors, a black wooden grid filled with translucent paper, can be pulled to – a wall of calm against the frenzy of mirrors and reflections, objets and ornamentation.

Graphic and unadorned, the levity of the Japanese washi paper is in stark contrast to the density and weight of the velvet drapes that adorn the walls, and that frame the windows and doors. Hefty swathes of chocolate brown, raw sienna and burnt umber; when drawn across, the floor-to-ceiling drapery creates what Mollino dubbed his ‘velvet submarine’ – a cocoon-like space where the soft, undulating textiles keep the world outside at bay.

A huge undertaking, the restructuring and renovation was no small feat, and yet, it was and remains, a rental property. With no partner, children or next-of-kin, Mollino would have had to assume that upon his death the property would be returned to the city of Turin, to be rented to the next occupant. Saved from this fate, the apartment, including all of its furniture and accessories, was taken into the care of Aldo Vandoni, an engineer who preserved it in its original state, using the space as his studio for more than 20 years.

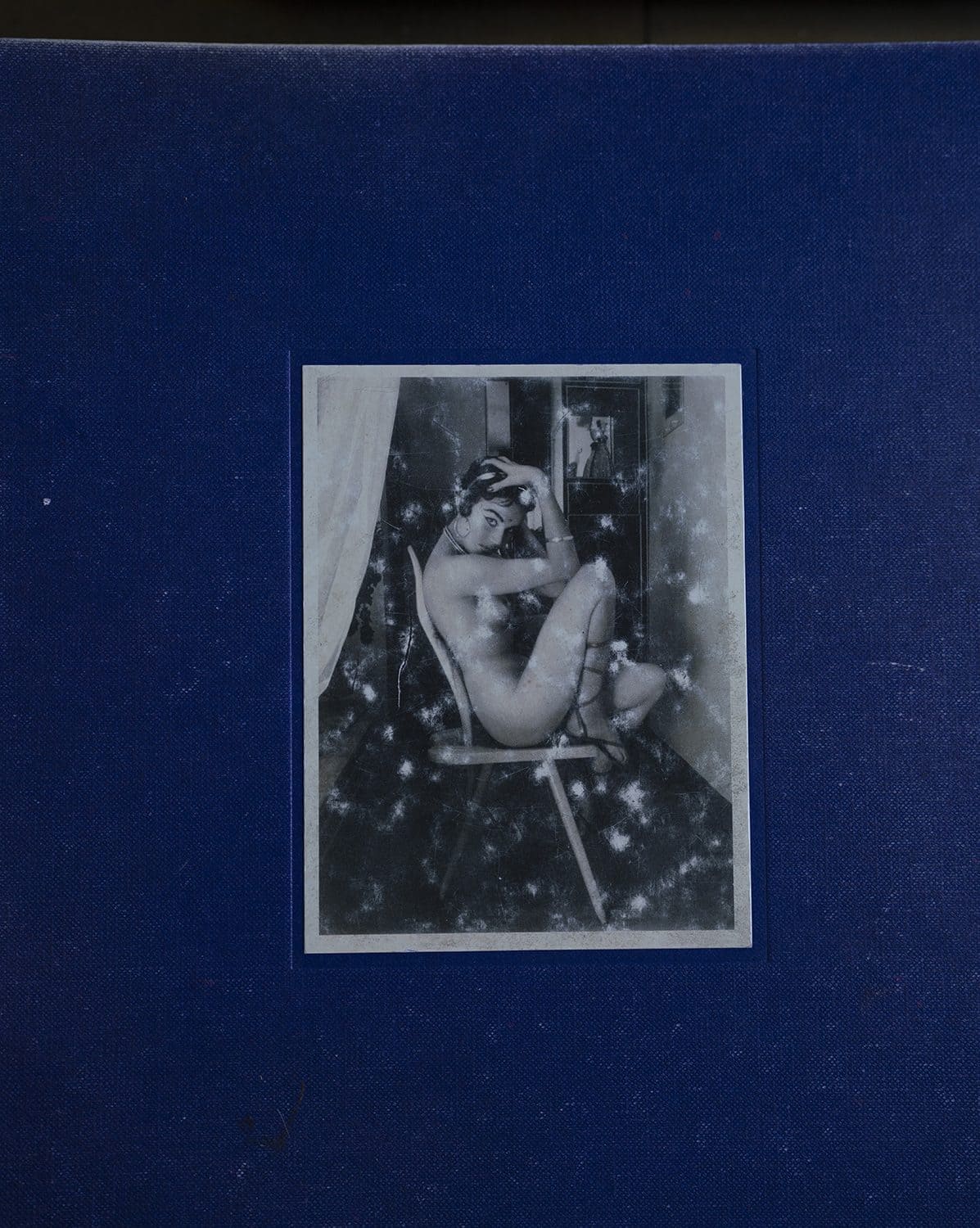

In 1999, Casa Mollino was established as a museum by Fulvio Ferrari and his son, Napoleone. Dedicated to the preservation and promotion of Mollino’s work, the Ferrari’s have undertaken in-depth research on almost every aspect of his life, publishing tomes that explore his interest in the physics of skiing and flight, the cache of polaroid portraits that were discovered posthumously, and the growing significance and mythology that has built around him since his death in 1973.