More Than a House

A morning with Xavier Corberó

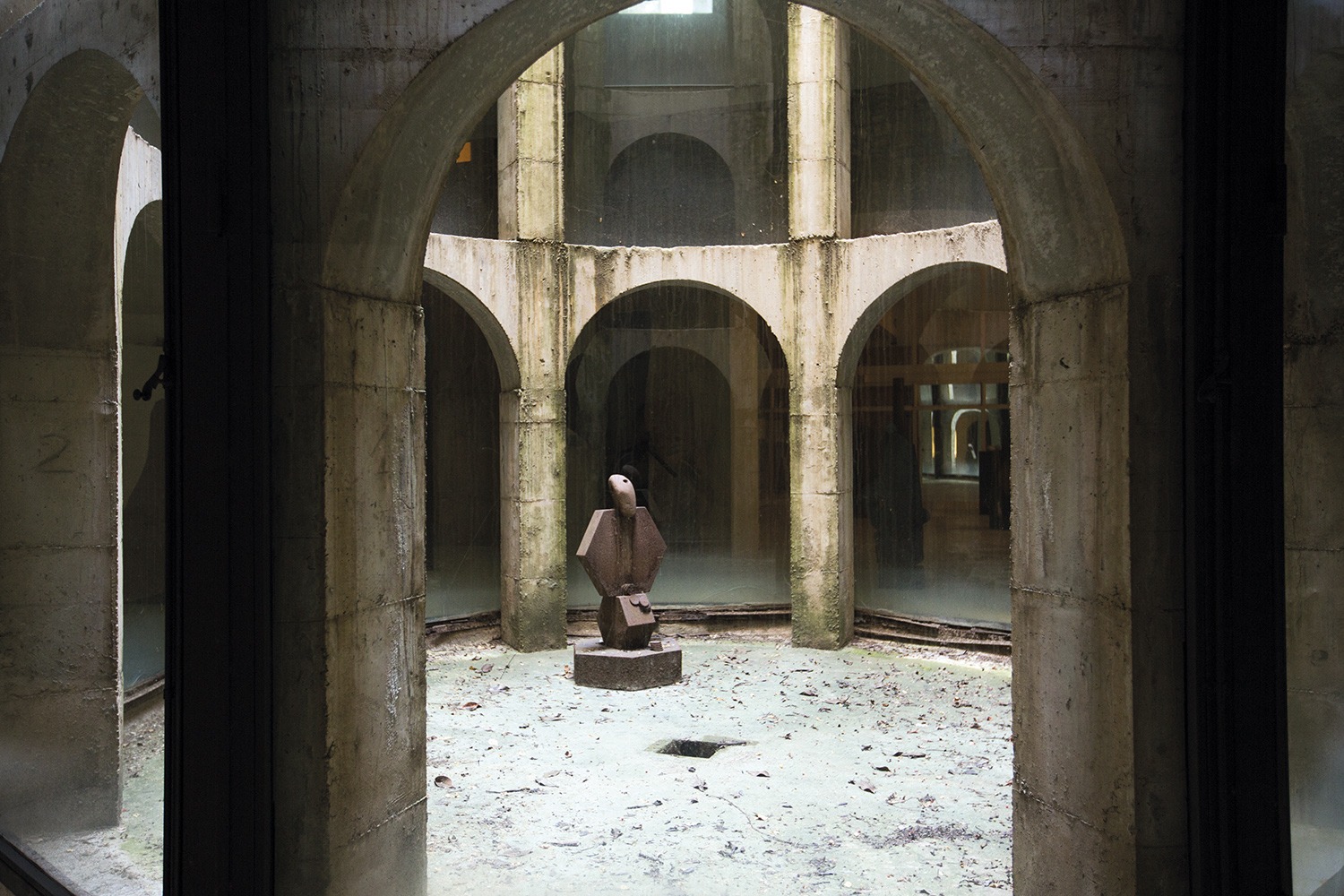

Colonnades, arches, and sculptures. I have been wandering amongst them for a while. I am together with the magazine’s team at Xavier Corberó’s place (Barcelona, 1935) on a husky autumn morning. They whisper instructions and ideas to each other as they take pictures around the concrete porches on the patio. The sound of water echoes from a pond and a conclusive fragrance of gardenias fills the atmosphere. There are families of sculptures made from rough stones, brutal creatures leaning slightly as if they were having a chat.

Photographer Mari Luz portrays precious elements arranged around the architecture. Yanina, Andrew, and Diego stay close to her, seeking the best light. Observed from a few meters away it appears as if, at anytime, their figures could begin to levitate. I can’t tell amount of time we spend in the courtyard… But everything seems to rush when the bells from some church nearby ring solemnly, twelve times. We’re about to meet the master.

We cross a car park where iron shells are embedded in the ground. Guided, we go through doors that open and then close again, climb a flight of stairs, and then turn downward until we reach a warm room. There are carpets everywhere, and the wooden floor and ceiling stain the light into a creamy colour. In the centre, a lantern filled with those infinite arches. Mozart sounds as if there were an old record player in the room above.

We wander, as in a museum, (and perhaps we are in a museum), admiring the group of sculptures on display around the room. The artist, Xavier Corberó, waits behind one of them. Formal presentation. He wears red socks, a burgundy jacket with an old-school handkerchief in his pocket, and a pin in the shape of a tiny star holds his tie.

Until this moment, I was not sure whether I would be able to meet the architect of the whole world, and now I am neither sure if he will agree to sit down and answer my questions. But he seems friendly and accommodating. He sits behind a large table full of objects and invites me to do the same at the other end. We have little time to talk, but his sentences are strong and categorical, characteristics that seem shared with what I have seen of his work.

I ask about his home.

“More than a house, it is a place, a PLACE” he stresses, “that has arisen from a total need: spiritual, emotional, physical… Which, ultimately, serves to cover the ugly. I do not believe in property, nor in artists’ colonies. In the end they are only centres of self-congratulation. I do not believe in universities either, people generally come out of them so lost.”

I am interested in knowing more about how, over the decades, he has turned the place into a reception centre for artists.

“All kinds of people have lived here, such as Robert Hughes or Elsa Peretti. The trick in life is to grow, which means to become self-sufficient. In order to achieve that, you need to follow a path and, before this, it is necessary first to find it. All of this takes time. Time. This is what we gave to the people who lived here. No rules. Well, just two: stay a minimum of two years and do not talk about art”.

He must have noticed the raise in my eyebrows.

“It is not that I do not like to talk about art. But I don’t like it when it becomes so institutionalised because this limits it within itself. I prefer to talk about the things that really matter in life, such as the weather, if food is nice, if you have the flu, or if you slept properly.”

I ask, “Then you will not like it if I ask where you think lays the border between architecture and sculpture?”

To that he answers, “Borders do not exist, and are often only invented and a big nonsense”.

He lights a cigarette; the smoke is dense and it curls among the sculptures that surround him. I take this opportunity to ask if he believes that the way he has helped other artists has turned him into some kind of patron.

“No, I just consider myself normal. It is normal to help other people. The matter here is that this seldom happens”.

Time is running out, but I must keep inquiring. Where does this person come from? “Please, could you briefly tell me about your childhood?” Smoke thickens in front of his face as he reveals, “I was born before the war. My mother died when I was very small. During the bombings in 1938, I used to run to the shelter on my own. I was three years old. The sirens would ring and I was told: You are Xavieret Corberó i Olivella, and you live in Claris, 40”. He takes a deep, dramatic pause. “The worst thing that can happen to you in life is not having problems”.

And so the doors, perhaps, might remain open.