Many Lives Under One Roof

Richard Neutra’s VDL House

Being handed the keys to a Modernist architectural icon is no easy feat for any mustering design enthusiast, and the current custodian of the Van der Leeuw Research House, Professor Sarah Lorenzen, has taken the honour on, foibles and glory alike.

Sarah’s background as an Architect and Professor based in Los Angeles made her a perfect fit to take on the heaving task of restoring Richard Neutra’s VDL House to its current-day glory. Her period in the house has seen it through structural and architectural restoration, extensive community engagement, and the creation of an Artist Residency program, amongst some of its many accolades.

Richard Neutra’s career as a Modernist North American Architect saw the VDL House as an experiment of types, with the intent to accommodate his own office and two families at any one time. Since the initial design and inception by Richard and his wife Dion, the house has become an epicentre of experimentation, exploration, design, and life conversation; an important legacy Sarah is well suited to fulfilling. We had the pleasure of an audience with this fine custodian, to discover more about her connection to this humble icon.

The house was donated in 1990 by Dion Neutra, with the goal of being a resource to learn more about the architect and his work. It is currently owned and under the stewardship of California State Polytechnic University in Pomona. The property is maintained by the College of Environmental Design, where Sarah herself is a Professor, and spans over 390 sqm.

When Sarah began there was minimal funding and, “The house was in disrepair but, fortunately, no structural issues with the house, despite some water damage issues,” she says. VDL was “designed to be a dematerialised house, with the roof and walls, and a lot of overlapping surfaces and overhangs, not designed with the water flow in mind. Technology has gotten better and all the things they wanted to do, we can now do.” Through extensive efforts, “There is no sign from outside that anything has changed,” which in itself is quite the accomplishment.

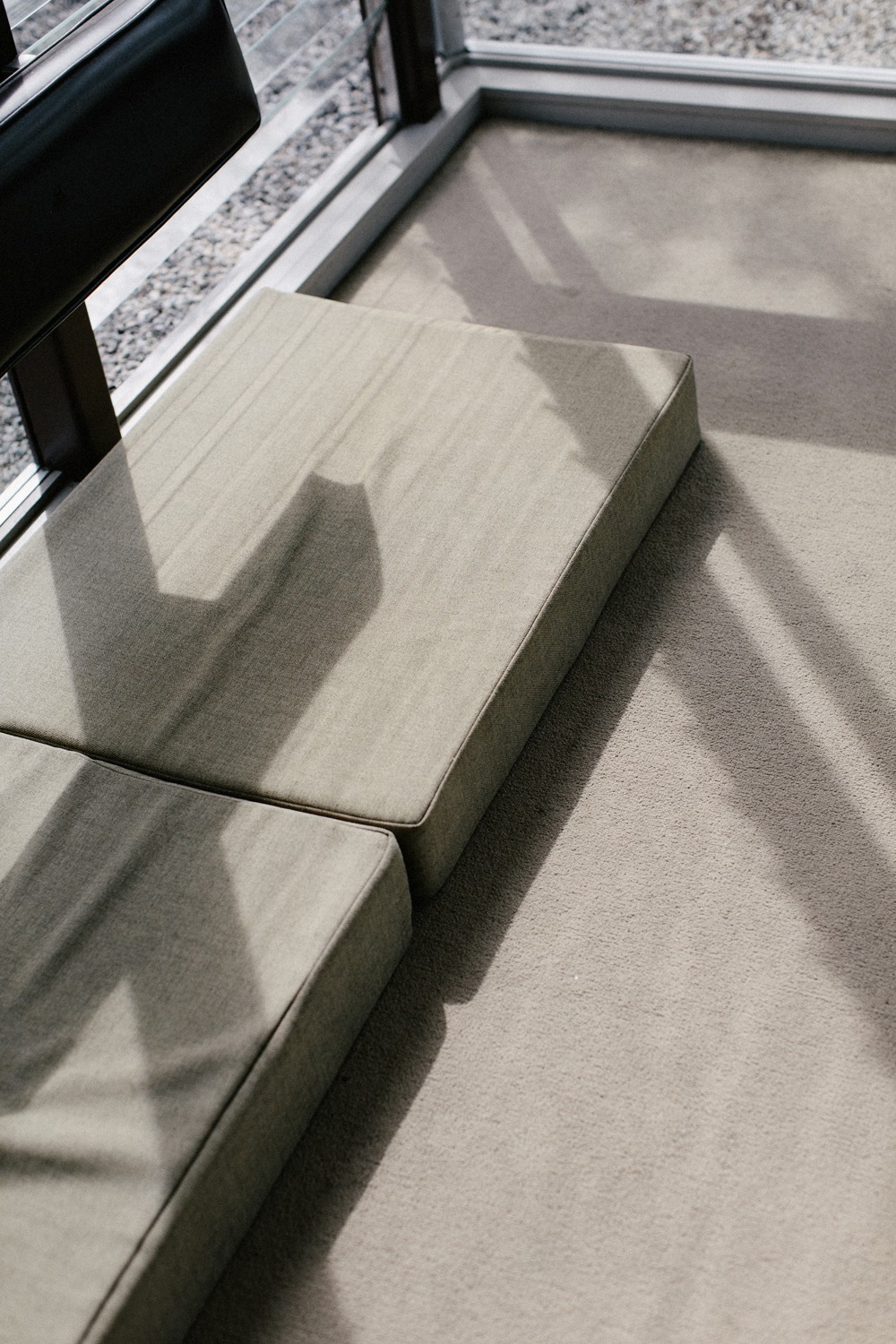

Neutra’s fascination with playing with how we mere humans live, his curiosities with our engagement with our spaces, is clear in his work, and never more so than in the VDL House. The design features numerous reflective surfaces, and façade and wall elements that diffuse the boundaries between ‘in’ and ‘out’. That there is no air conditioning and cooling system, Sarah tells us, is a marvel of intelligent design. “It’s not the house that has to change – you do. Temperature wise, it’s the same inside and outside and you don’t distinguish the differences.” Her time in the house has made her rethink the way we can perceive and experience space; “Everything is bouncing around, and you can’t notice where the light is coming from. It’s incredibly beautiful.”

Sarah explains that the VDL House “represents many illusions of his career. It represents early Neutra’s influence of the international style and European international style of Modernism in the U.S. The Garden house in 1939 was considered more Californian modernism, connecting inside and out. The 1965 house, the latter house, was more eclectic and the kind of the ‘end of modern.’” More specifically, VDL is a collection of “ideas and experiments. A very dense house with an office, apartment, family living, children, students in the basement, maids room, sister living there; a lot of people in a very small area. The house was about accommodating all of these uses and people. There are around 12 exterior doors to get in. The spaces are quite small, but a way to make it feel comfortable is to expand the space with mirrors, glass and reflecting areas; and always allowing people to have access to the outdoors. The exterior is an extension of the space.”

In terms of materiality, “What was also important was to use industrial, low-cost materials in an interesting way. Being his own house there are clever uses of formica, vinyl tiles, plywood and acoustical tiles, and stucco. It’s interesting how inexpensive all of the materials really are,” says Sarah, which seems ironic since “he built houses for really wealthy clients.” He also created homes “for normal people and low cost housing,” and there was opportunity for creativity, whoever the client. Neutra was apparently “always interested in using industrial materials in different ways, and had manufacturers donate materials in exchange for advertising, as a means to come in on budget,” and also to experiment in any way he could.

Like many of his colleagues in the Modernist era, there were a series of melting pots popping up, where creative juices were free to flow; architectural creative safe havens, if you will. VDL serves as such a pot. “The house is designed to live together,” Sarah says, and it stands today as it did in Neutra’s residency, as a mechanism for bringing his artist, architect, and other creative friends of the time together. This legacy has undoubtedly been respected and continued in the collaborations and programming of this current era at the house. “It’s quite unique for a city like LA, a post war city with single family houses that are all about living privately, without a lot of public interconnections. The goal is to repeat what Neutra did when he lived there. Similar to Schindler’s King Road House, used for parties, meetings, discussions, and programming, which fits well with the legacy. Essentially the house is a community resource,” Sarah says.

Inviting artists to engage with the house is an important part of this legacy. “The people who stay are artists, architects, and are all doing things. This is not about capitalising on the house, and not about giving opportunities to the highest bidder. They’re so grateful that they can share with others,” which creates this incredibly interesting community of sorts. “There’s a question of the priorities of the house, about opportunities to come together and talk, or to raise capital, and we need to find a balance.” She notes that, “It’s interesting how artists and architects respond so differently to the house.” The architects feel the weight of a legacy bigger than them, whereas the artists are encouraged to respond to the space and the experience of being there through their art.

Being at the core and being able to witness the reactions and responses of so many to living, learning and growing in such a space as the VDL, Sarah’s biggest lesson to date is her appreciation of the integration of landscape and architecture. She says, “It’s not about an object sitting in the landscape, but about the relationship to nature, plants, greenery, and other types of harder materials. This house isn’t designed as two separate ideas; they’re really one. It’s a lesson to architects and landscape architects to see space as a single idea, not as two separate disciplines.”

The importance of the VDL on Modern Architecture cannot be undervalued. “The house was not primarily functionalist as we understand modernism. It’s more about the experience, and the beauty that could benefit the residents psychological and mental wellbeing. He [Neutra] wrote about this a lot, about how the natural environment and the inclusion of the landscape and natural elements can benefit the way that we live.” Richard Neutra was an Architect before his time, tapping into the social spectrum of the human condition. He would sit, we imagine, happily content in the knowledge that VDL was in impeccably capable hands to continue this important legacy.