Heaven Knows

Fernando Higueras

c (marvellously reflected in Almodóvar’s film Pain and Glory) or César Manrique’s volcano home in the Canary Islands. In this way, Mother Earth became a proxy for the maternal womb.

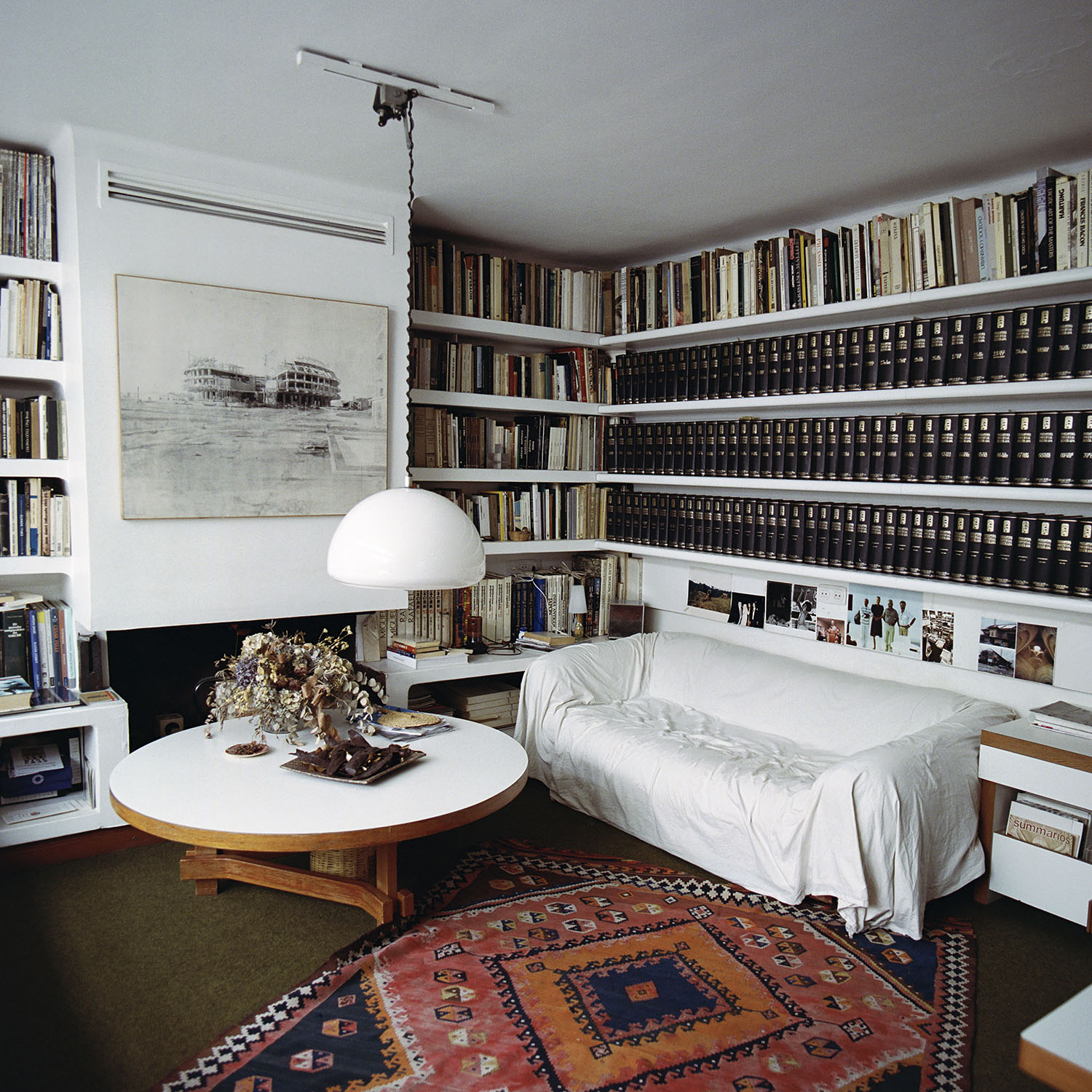

Following his divorce, architect Fernando Higueras–a close friend of César Manrique and one of the few Spanish exponents of Brutalism, an omnipresent trend that has seen a recent revival–found himself surrounded by conventional early 20th century villas whose only architectural aspiration was to provide accommodation. He thus decided to turn his back on the prevailing norms regarding living spaces and to build his new home below ground.

Higueras designed a new home in the style of a refuge on the plot of his former one in Colonia Albéniz, a garden-city suburb and protected area where new-builds and extensions were forbidden. It was a 9x9x7m underground cube, literally dug into the garden subsoil using spades and pickaxes because it was impossible to get heavy machinery onto the plots.

When you are inside that rascainfiernos (or hellscraper) as he called it, you are not at all aware of being below ground. A big double-height courtyard with a huge skylight made up of four smaller panes (from which plants from the garden used to hang when Fernando, who died in 2008, was still alive) ventilates and illuminates all the rooms, providing constant filtered light in a modern take on Paterna’s caves. Its architecture was not only clearly organic but also metabolic, adapted to its user’s new living requirements.

At a point in his life, from the 1980s onward, when Higueras started to receive fewer commissions, the underground refuge became his private film set for making pornographic movies (as he himself said in an interview). Those hundreds of minutes of film are the only records of what went on there: episodes in which, like Onan in the Book of Leviticus, seed was spilled on the ground. (In the Bible, Onan was punished for wasting his seed instead of using it to procreate). Nonetheless, Fernando Higueras felt protected. Whatever his sin was, the only witness was the sky above in the Madrid heavens. Obviously it was eccentric to cut himself off from the rest of the world so that he was only accountable to the luminous guardian-like sky, but then much of his voluptuous provocative architecture tied in with Higueras’ hedonist over-the-top approach to life and his relations with the world.

What induced a successful architect to live below ground? Are ideas that are hatched in caverns more personal than those conjured up on the surface? Is seclusion from the rest of the world, or secrecy somehow comforting?

That home-cum-ideas-cavern probably marked a turning point in his creative work, with architecture becoming mixed in with his own life. We were unable to locate any of the rolls of film of those amateur erotic movies he claimed to have made, but their mere mention was doubtless a form of evasion, an exercise in escapism, and a sublimation of his ambitions as a creator. What could be more sensual–or brutal–than to incarcerate yourself below ground and to give free rein to your innermost desires, not just carnally but also in creative terms?

The underground home has continued to add to its notoriety as a testing ground for expressing and deciphering desire. In the installation Intimate Strangers, Andrés Jaque and his Office for Political Innovation chose Higueras’ hellscraper as the basis for reflections on the geolocation apps used by social networks to organize sexual hook-ups, in particular the gay-oriented Grindr. A paradigmatic transnational sexualized city planning app, Grindr’s intangible architecture nourishes a specific geolocated space and network of desire-driven contacts, encounters and sociability.

Are we able to manage desire better from a hiding place? What virtuality is offered by the social networks we generally use from our own caverns? Has our relationship with pleasure changed in recent decades?

Filming erotic movies, using social networks to foster furtive sexual hook-ups, hiding away in order to find oneself…these things can be done in endless different places, but only some lend a special twist to such activities. The hellscraper reveals its role as a centre for worship and prayer, a pagan chapel, the very best of places to be yourself, to devote yourself to hedonistic pleasure and to the priesthood of the libido under Madrid’s guardian-like sky.