A new dawn for artists James Russell and Hannah Plumb of JAMESPLUMB where the heaviest works demand the most subtle of interventions.

The creative studio of JAMESPLUMB has expanded and contracted naturally, a steady growth of both team and projects making objects and environments (Hostem, Hermès, Aesop, PSLab) since its founding in 2009 by the artists James Russell and Hannah Plumb. Shortly before the pandemic took its hold, the pair found themselves in need of recalibration, a pause to exhale, and so scaled down. I meet James and Hannah while in the process of expanding once more, on a personal level with their newborn son, Walter, and sights set on a move to Shropshire.

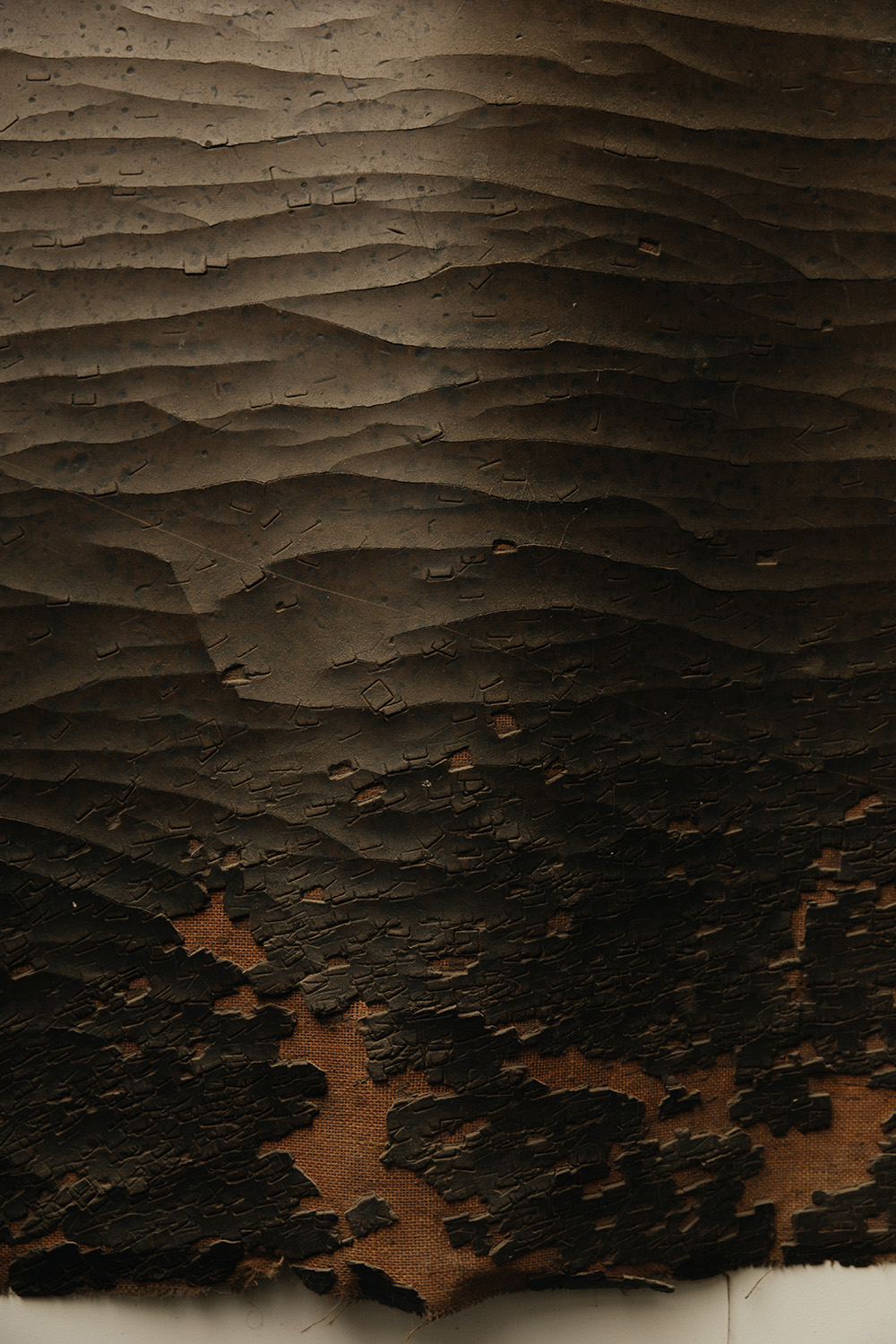

Inevitably, the contemporary struggle with real estate and its impact on growth and creativity is discussed; they later share with me a work in progress (inspired by Leo Tolstoy’s short story ‘How Much Land Does a Man Need’) Pahom’s Graves (2019). The 20th century oak door frame and steel unique piece considers the geometry of beatification, ‘The mathematical proportions used to calculate the space to afford a human body in the grave is applied to objects on the very edge of life.’ The work of JAMESPLUMB applies itself as sensitively to what it means to live, as it does to how something inanimate might.

People probably know us more for our objects that cross the line between furniture and artworks. On one hand we see we’re making a piece of sculpture, but then it also has to function as a chair; getting that balance right, because we want it to function, but it has the poetry, the tension and essence that got us excited.

The pair met a decade prior to establishing their studio, as students at Wimbledon College of Arts in London. While developing concepts through materials and process exploration, they also developed a form of short hand in communicating with each other, and have often found themselves recording the same moments. While two perspectives on the same memories might not be unusual for any couple who have known each other for more than twenty years, the depth of consideration and the freedom of thought that earmarks their work, which avoids a self imposed separation between art and design, makes such a synergy all the more remarkable.

A lunch of watermelon and feta salad is served at the generous table that the couple lay with ease in their high-ceilinged Camberwell workshop, previously a water storage facility. As we settle in, Hannah shells broad beans grown by her sister, while Wilfred, their terrier, quietly rouses and ambles over to greet us, before disappearing again. Just as the rhythmical shelling sets the gentle pace for our conversation, and the careful placing of empty pods helps to build a picture we gather to snap, to break bread with artists so well honed in their expansive craft is a sensory experience to savoured, providing you are able to follow a lead they may – somewhat inadvertently – take.

As we settle in, Hannah shells broad beans grown by her sister, while Wilfred, their terrier, quietly rouses and ambles over to greet us, before disappearing again.

I remain curious to know how, time and again, they balance the artistic with the practical, “I think it does go to the heart of quite a lot of what we do,” says James. He continues, “People probably know us more for our objects that cross the line between furniture and artworks. On one hand we see we’re making a piece of sculpture, but then it also has to function as a chair; getting that balance right, because we want it to function, but it has the poetry, the tension and essence that got us excited. It’s so easy for it to tip one way or the other. I can’t give an answer as to how we resolve that, other than we’re quite uncompromising; it has to meet both those and if it doesn’t meet one, then we won’t make it.”