Rosa Park

Rosa Park, Director of Francis Gallery, has an intimate understanding of objects – an intuition for materials and meaning that presents itself in subtle and affecting ways. A skilled and sensitive curator, Park’s galleries in Bath and Los Angeles are a template for how to live with art.

Exploring ideas of intimacy and domesticity, for Park the gallery is an experiment in setting and scene. Looking to artists and collectors – citing institutions such as Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge and the homes of Donald Judd and Georgia O’Keefe – Park introduced antiques, furniture and design pieces into the space, as companions for the paintings, ceramics and sculpture.

PORTRAIT OF ROSA PARK

PORTRAIT OF ROSA PARK  PERSIMMONS. Persimmons by John Zabawa captures the fruit I most associate with my home country in his trademark intimate, warm manner. Each time I walk past this painting, I think of the connection between this work, created in LA, and Korea; a place where John and I share mutual ancestry. DESIGNER: JOHN ZABAWA.

PERSIMMONS. Persimmons by John Zabawa captures the fruit I most associate with my home country in his trademark intimate, warm manner. Each time I walk past this painting, I think of the connection between this work, created in LA, and Korea; a place where John and I share mutual ancestry. DESIGNER: JOHN ZABAWA.A mise-en-scène, each exhibition is a conversation between the artist, the objects and the space. Speaking with Park, I am reminded of the Gesamtkunstwerk – the 19th century concept of the ‘Total Work of Art’ – whose aim was to create a single, cohesive whole. Encompassing time, place and context – art, architecture and design – in the Gesamtkunstwerk each element enhances the other.

THE CAMALEONDA SOFA. The Camaleonda has become popular to the point of being a caricature of itself. Nonetheless, I remain an ardent fan of this sofa designed by Bellini. It holds a special place in my heart, not only because my partner and I worked on the B&B Italia campaign that launched its re-issue, but also because it is the ideal sofa for a toddler. My two-year old son loves the Camaleonda! DESIGNER: MARIO BELLINI. BRAND: B&B ITALIA. YEAR: 1970.

THE CAMALEONDA SOFA. The Camaleonda has become popular to the point of being a caricature of itself. Nonetheless, I remain an ardent fan of this sofa designed by Bellini. It holds a special place in my heart, not only because my partner and I worked on the B&B Italia campaign that launched its re-issue, but also because it is the ideal sofa for a toddler. My two-year old son loves the Camaleonda! DESIGNER: MARIO BELLINI. BRAND: B&B ITALIA. YEAR: 1970. The gallery in Bath has been beautifully restored: replete with moulded wall panels and ornate cornicing, dark stained floorboards and generous wood-framed windows, its Georgian interior is the antithesis of the ‘blank slate’ or the ubiquitous ‘white cube’. Park notes that she doesn’t “have to work hard to make [this space] feel like a house,” and so, over time, she has developed a looser curatorial approach, using furniture and other objects more sparingly – to great effect. The pieces that remain are a reminder that good art, like good design, will last the test of time.

When I visited in early 2023, an exhibition of paintings and ceramics by Rosemarie Auberson was on display. Fields of colour and tone – each canvas boasts areas of dense, impenetrable pigment alongside thin, layered washes. Hung like musical notes, the paintings punctuate the space, drawing you through it… A small painting in soft, pink tones hangs beside the fireplace – itself a piece of contemporary sculpture with a gentle, curved hollow and rough papery finish. Off-centre and below eye-level, the painting’s position accentuates its tenderness, and the vulnerability of Auberson’s surfaces.

Like many of the artists represented by Francis Gallery, Auberson rewards the contemplative viewer – those who sit with the piece, returning to it over and over again. Speaking with Rosa after my visit, she notes that the artist takes each painting from the studio into her home, living with it for months – observing how it changes as the sun rises and falls each day – before she decides if it is complete. “When I found out about her process it made so much sense. I am very interested in the domestic scale of things, and so the way she works really resonated with me.”

GOURD SHAPED CERAMIC WIND INSTRUMENT. For Turner's birthday, artist Nancy Kwon made a ceramic wind instrument shaped like a gourd. There is something about the form of a gourd that I find infinitely inviting and beautiful, and her talent and thoughtfulness in making an original musical instrument for my son blew me away. DESIGNER: NANCY KWON. – A BEAR CARRYING A SATCHEL ON THE BACK MADE OF TURQUOISE. My Navajo fetish from Shiprock Gallery in Santa Fe is of a bear, carrying a satchel on the back made of turquoise. I cherish objects imbued with a sense of spirituality, and this little object has such a powerful pressence. GALLERY: SHIPROCK GALLERY. – WEDDING DUCKS CARVED FROM WOOD. When a Rich and I got married, my parents gave us wedding ducks carved from wood. In Korean culture, newly weds are traditionally gifted a pair of wedding ducks; they simbolise peace and fidelity.

GOURD SHAPED CERAMIC WIND INSTRUMENT. For Turner's birthday, artist Nancy Kwon made a ceramic wind instrument shaped like a gourd. There is something about the form of a gourd that I find infinitely inviting and beautiful, and her talent and thoughtfulness in making an original musical instrument for my son blew me away. DESIGNER: NANCY KWON. – A BEAR CARRYING A SATCHEL ON THE BACK MADE OF TURQUOISE. My Navajo fetish from Shiprock Gallery in Santa Fe is of a bear, carrying a satchel on the back made of turquoise. I cherish objects imbued with a sense of spirituality, and this little object has such a powerful pressence. GALLERY: SHIPROCK GALLERY. – WEDDING DUCKS CARVED FROM WOOD. When a Rich and I got married, my parents gave us wedding ducks carved from wood. In Korean culture, newly weds are traditionally gifted a pair of wedding ducks; they simbolise peace and fidelity. YOLK BOWL. I am obsessed with my Vincent de Rijk Liquidish bowl in yolk. It emanates sunshine and joy. DESIGNER: VINCENT DE RIJK LIQUIDISH.

YOLK BOWL. I am obsessed with my Vincent de Rijk Liquidish bowl in yolk. It emanates sunshine and joy. DESIGNER: VINCENT DE RIJK LIQUIDISH. In 2022, Park opened her second space in Los Angeles – for which she has adapted the gallery’s model to account for the architecture, history, scale and palette of her new locale. A reflection of her evolving interests, the US gallery will continue to develop the same themes as the first within a new context: “I worked very hard to create intimacy [in the LA space] – I built a partition wall that’s curved so that the single giant room is broken up into four quadrants, and within that curve we wanted to create a temple- or altar-like experience… I am still exploring the themes of intimacy and domesticity, but not in a literal way – more in the sense of how it makes you feel.”

AKARI LAMP. I can't get enough of Noguchi Akari lamps. I got them all over the house – as pendants, floor lamps, table lamps; in our room, in Turner's room, in the dining room and living room. The soft glowing light, the weightlessness, and the sculptural nature of Akari forms keeps me coming back for more. DESIGNER: NOGUCHI AKARI. BRAND: VITRA. YEAR: 1951.

AKARI LAMP. I can't get enough of Noguchi Akari lamps. I got them all over the house – as pendants, floor lamps, table lamps; in our room, in Turner's room, in the dining room and living room. The soft glowing light, the weightlessness, and the sculptural nature of Akari forms keeps me coming back for more. DESIGNER: NOGUCHI AKARI. BRAND: VITRA. YEAR: 1951.  19TH CENTURY MINHWA PAINTINGS. This pair of 19th century Minhwa painting, which I acquired from a dealer in the UK. They are framed to perfection – sage green, raw silk matting with an antique brass frame. I appreciate what Minhwa paintings represent – of the people – and love having this piece of Korean art history in our space. DESIGNERS: MINHWA. GALLERY: FRANCIS GALLERY.

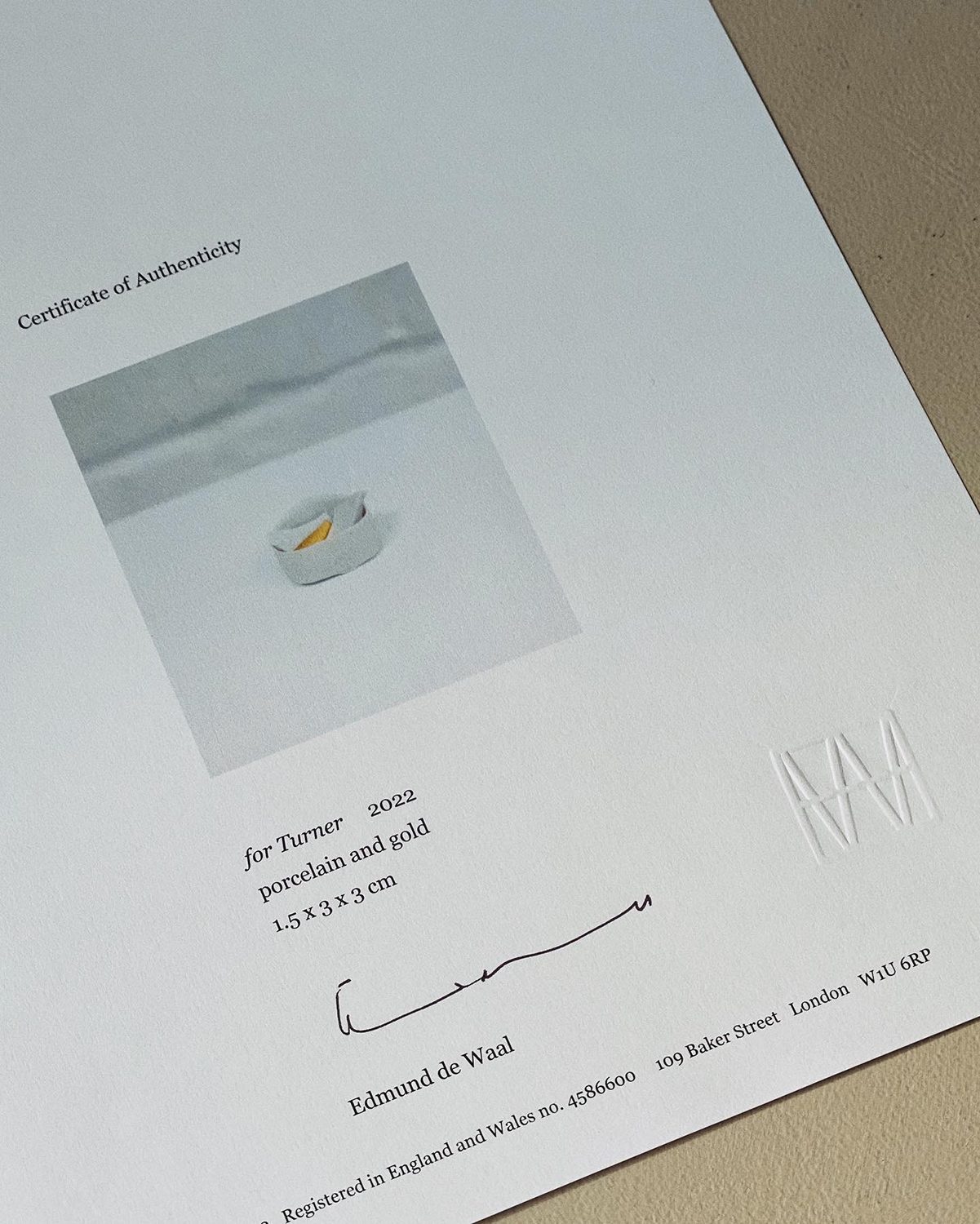

19TH CENTURY MINHWA PAINTINGS. This pair of 19th century Minhwa painting, which I acquired from a dealer in the UK. They are framed to perfection – sage green, raw silk matting with an antique brass frame. I appreciate what Minhwa paintings represent – of the people – and love having this piece of Korean art history in our space. DESIGNERS: MINHWA. GALLERY: FRANCIS GALLERY.  FOR TURNER. One of my favourite artists, Edmund de Waal, created a small work from our son and titled it For Turner. I was speechless when it arrived in the post, and I can't wait to share this with Turner when he's a bit older. Until then, the work happily lives in our vitrine. ARTIST: EDMUND DE WAAL.

FOR TURNER. One of my favourite artists, Edmund de Waal, created a small work from our son and titled it For Turner. I was speechless when it arrived in the post, and I can't wait to share this with Turner when he's a bit older. Until then, the work happily lives in our vitrine. ARTIST: EDMUND DE WAAL. Speaking from LA, Park notes that she, “changes constantly – always interested in the next thing,” and yet, far from being fickle, her philosophy is more akin to the practice of Kintsugi – the Japanese method for repairing broken pottery with gold, its newly veined surfaces acting as a reminder of its own history. “Things are meant to break over time, nothing lasts forever. That’s not to be flippant – in fact, it’s the opposite – it’s because I have so much love and respect for these things that I want to be with them every day.” Park’s approach is shared amongst her artists, each of whom embodies and interprets the philosophy in profound and personal ways, producing work that explores ideas of time, age and wear.

Drawn to impermanence and imperfection, Park is attracted to patina rather than gloss, intricate layers over exuberant forms. Seeking objects whose aesthetic merits are equalled by their meaning, she places great emphasis on the stories that attach themselves to objects – the grand, or personal, narratives that transform a simple object into a memento, token or heirloom.