In a short period, Gabriel Hendifar and Jeremy Anderson have turned Apparatus into one of the world’s most feted interiors brands. We visit their New York studio, where they still make all their designs, to find out what makes them tick.

Life seems to happen to Gabriel Hendifar, the co-founder and creative director of Apparatus, in such an organic way that you wonder if he’s lucky, charming, or destined – or all three.

Take his first job, for example, with Los Angeles-based designer J Mary, who makes bespoke womenswear. She offered him a role after spotting him in a fabric shop buying buttons, even though he had no formal fashion training (at the time he was still an arts student at UCLA specialising in costume design). “That became my real education,” he says. “I learned about making, because we were taking vintage pieces apart and putting them back together, and I also got to understand what it means to create clothes for people who can have whatever they want. How do you make a one-of-a-kind dress that somebody decides they have to have, regardless of the cost?”

This focus on hand-crafted production, and perfection before price, is something Gabriel took with him to Apparatus, which he created, almost by accident, with his boyfriend (now husband) Jeremy Anderson a decade later. “We met in Los Angeles and moved in very quickly – after six months – and part of that became looking for lighting, and part of looking for lighting became, in all honesty, not being able to afford what we liked, or not liking what was out there,” he says. “So, we decided to make our own. I remember saying, ‘I think there’s something we can do, that doesn’t exist,’ and Jeremy has boundless energy and he’s so good with his hands, so he was like, ‘Yeah, let’s do it!’”

Their first design was the Twig light (a ceiling track with branch-like articulated arms coming off it), followed by the Cloud chandelier (a cluster of glass orbs hanging from chains, which look as light and joyful as a bunch of balloons). Both caught the eye of a friend who was visiting for dinner, who also happened to run a furniture and lighting gallery in Los Angeles. He asked if he could stock them, and within 18 months they had a few orders, a trickle of press attention, and enough interest after exhibiting at a trade show that they decided to open a studio in New York, where they had relocated, and quit their day jobs (Gabriel was working with fashion designer Raquel Allegra, and Jeremy worked in media relations).

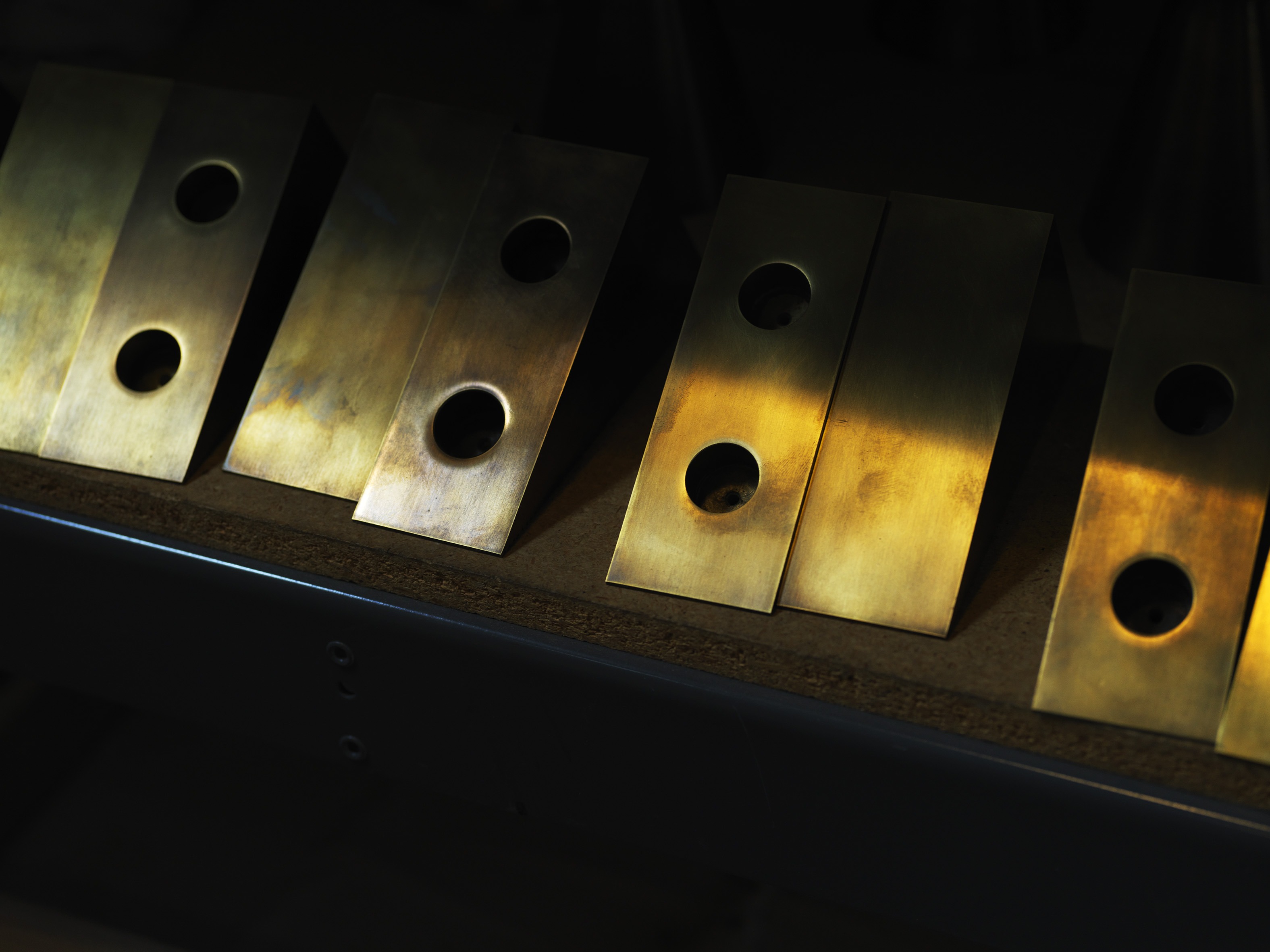

Although they didn’t realise it at the time, these two pieces established what the brand would become known for: designs that are as offbeat as they are exquisite, where the use of unexpected or opposing materials is as important as the function. “We are invested in the language of simple geometries – clean squares and circles – but we try to express this with materials that don’t want to be precise or mathematical,” explains Gabriel. “If you try to make a circle from porcelain, it’s never going to be perfect, and that vulnerability makes the work feel like it has a soul. There’s an almost tragic distance between the idea and the actual thing.”

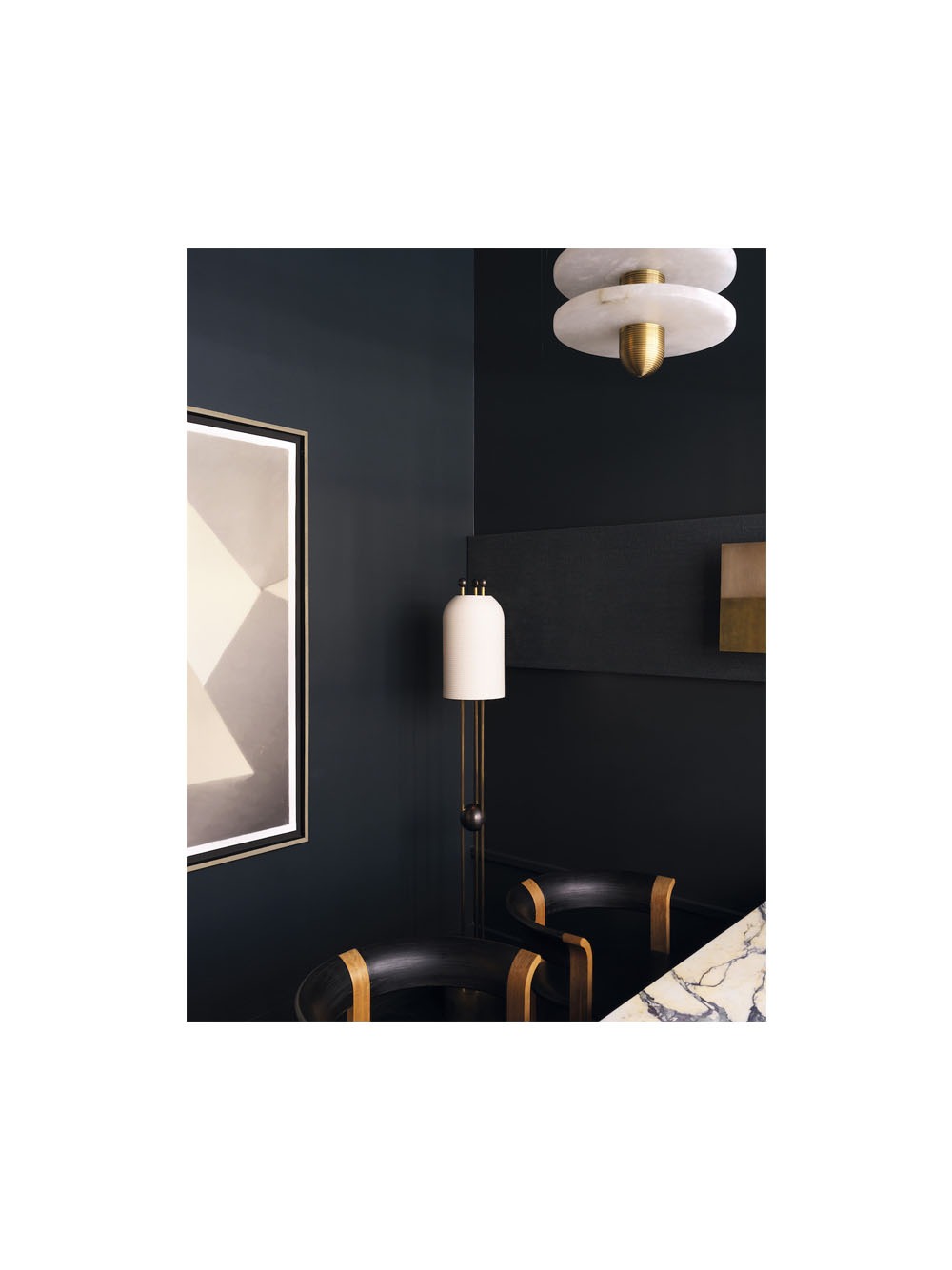

Today, almost six years to the day after they quit their jobs, all designs are made and sold by a staff of 46 in a 10,000 square-foot studio and showroom in Midtown Manhattan, where they moved nearly three years ago. It’s a sprawling and opulent space, which they redecorate each season like a giant theatre set to showcase the new collection. (It’s no surprise that when Gabriel was a teenager, he designed the set for his high school’s play, which turned out to be the most expensive it had ever built.)

Inside is a study of contrasts, where product and production sit side by side. The entrance room is pure plush, with carpet-lined walls and perfectly placed furniture, while in a long workshop next to it, a team of six assemble every nut, bolt and fixture for every piece. In two small rooms at the back, a team of artisans work on all the metal finishes and soft materials, such as leather, and in the sales room there are wooden vessels from Kenya’s Turkana tribe piled high against a wall, which customers can choose as shades for the Bowl sconce. At first glance, they look like a macabre trophy of old skulls or helmets.

It’s an unusual approach for a business in an era of fast design and outsourced manufacturing, but for Gabriel and Jeremy, who now shapes the brand’s bigger strategic moves, such as the upcoming launch of a Los Angeles showroom, the benefits outweigh the challenges. “Everything we do, we are figuring it out as we go along, and we have come to realise the power in this, because it gives us control over the entire experience, right down to how we pack our boxes,” he says. “We want people to feel like they are buying something that has been touched by humans, and something that is worth keeping in their lives. We want our products to have a little bit of magic dust.”

Apparatus also works with makers around the world to create various components for their designs, which are then shipped back to New York and stored in the studio. The ridged porcelain shades for the Lantern lights, for example, are made by a family-run ceramics factory, which has been in continuous business for 300 years. “These vendors allow us to dream of things that we don’t know how to make, and a big part of my job is to seduce them. It’s a process of saying, ‘Here’s what we want to do. We might be pushing you out of your comfort zone, and it might fail, but how amazing would it be if it succeeds?’ And the most gratifying thing is that we now hear yes more than we hear no.”

The latest collection, Act III, includes lights made from beads of semi-precious stones, like oversized chunky necklaces, and bowls made with intricate Persian marquetry. It’s Gabriel’s most personal work yet, exploring the gap between Iran – the country his parents are from – and America, and he is particularly proud of the designs. “For me, expressing a narrative through a collection has become the most inspiring thing, because it’s a way to leave a deeper impression on people and say something about the wider world,” he says. “Design doesn’t live in a vacuum.”

So, what do Apparatus’s designs say about the world now, at a divisive time of border walls, trade wars, and an uncertain world order? “It’s interesting, because the last few collections have all looked back at the extravagance of these end-of-empire moments, such as 1930s Europe before the war, and 1970s Iran before the revolution, and I think we are experiencing something similar now,” says Gabriel. “There is a decadence, and it feels like it could signal the end of something, and perhaps the beginning of something dark.”

It’s a foreboding Rome-before-the-fall thought, and one that Gabriel finds both conflict and comfort in. “I have some guilt about the fact that ultimately, we are making more things, but finding these moments of historical context reminds me that this is part of how we tell our story as humans,” he says. “The material culture is what we leave behind, and for better or worse, it’s the only way I know how to make some sort of imprint on the world.”

There is something else Gabriel says, however, that speaks more about the power and purpose of design, on a personal level. “I remember my mother’s cousin as a very young kid. She was this creative woman who did needlepoint and made pillows, and I remember being starry-eyed at all these things in her apartment,” he recalls. “That’s one of my first memories of what it means to … I guess, design wasn’t a word I knew at the time … but to want to make something beautiful.”