When one thinks of “living in nature”, the images that come to mind are a range of shelters (from tree houses, tents, and cabins to chalets and estates), the scale and architectural envelope of which may vary depending on fantasy and resources. However, the location in “nature” is a less broadly imagined spectrum: it is probably gentle (sea breezes); soft (sloping grassy rises); moderate (filtered, shaded light); reassuring (materially contained).

When modernist architect Luis Barragán and his friends started to hike in the El Pedregal area of Mexico City, they must have lurched, stumbled, twisted, and scraped their bodies over the hard, uneven, grating, sharply textured lava fields that define this area. In the early 1940s, this was a zone outside—outside of urban development, and to some degree colonial histories—because of its inhospitable nature. And yet, enduring that recreational abuse, Barragán did not retreat, but instead envisioned a community of homes—an architectural project that aspired to integrate urbanization (a large-scale housing development) and ecosystem protection (sites were carefully excavated rather than leveled). Designed and built between 1947-1950, one of the first homes was Casa Pedregal.

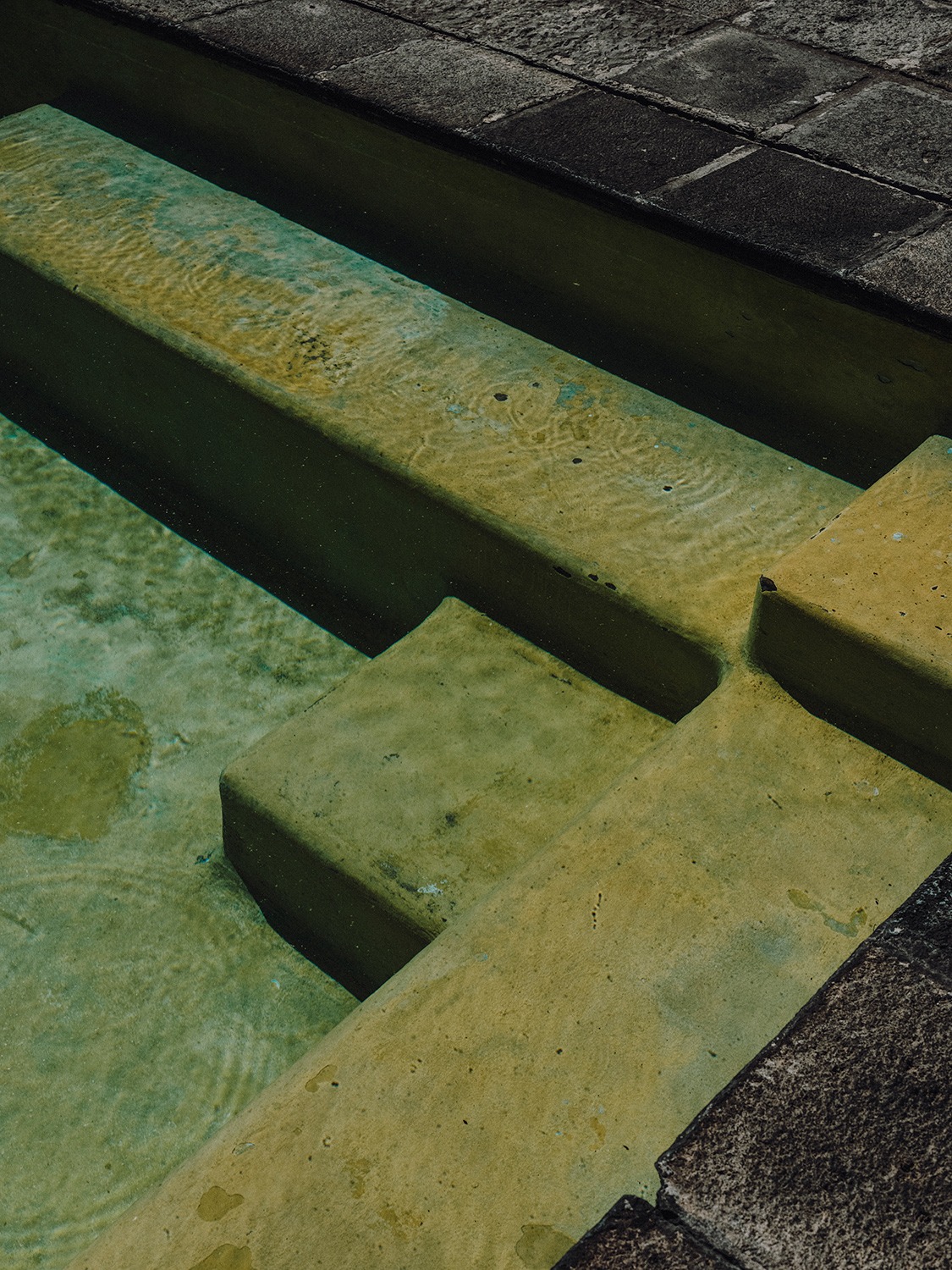

As a mediation on, rather than defiance of, the topple surfaces of the location, the home expresses balance—not just in the abstract design plan, but in its human proprioceptive invitations. Deep low-riser steps assure room elevation transitions that in turn respect the original footprints of the lava deposits, mitigating but remembering the site’s geology. Clarity of modernist geometries shape volumes and define fenestrations, gridding a sense of measure, repetition, and modularity that create reassuringly predictive spaces.

Large continuous and expansive surfaces (hardscape stone pavers, interior wood plank floors, reflective ceramic tile walls) reorder a life surrounded by nature’s regurgitated upheavals. Large glass windows and doors visually unseal the home with views of a scabbed, crusted-over natural environment. Angling patterns of light and shadow record time even as the lava fields freeze it in primal gesture. This is architecture of actively engaged equilibrium rather than passive coziness.

Throughout, the specific language of Barragán’s Mexican modernism moves from intelligences of form to the senses of eye and hand. Vision-absorptive planes of rose-pink stucco rise as backdrops to outcroppings of lava, ferns, cacti, and thistles originally left during foundation work. Inside, the palette slightly mutes to wall-fields of sienna or teal, cool greys and warm beiges. Slabs of wood (custom tables, cabinets, credenzas) forest the rooms; leather-slung butaques scoop light even as they anticipate human weight. Everywhere there is the intimate amplification of equilibrium.

Cervantes identifies the pleasures and “infinite lessons”—often the same—of living in this house. It is a home in which spaces are undefined until animated by human activity, rather than rooms pre-designed and confined by specific functions: “The living room one night, from the joy of being here together, spontaneously becomes a full dancing room, and the next day my kids and their friends convert it into a roller-skating room. And we have had huge parties also, 300-plus people in the space, and nothing [no damage] happens. It is so gentle, so simple—it’s beautiful.”

The exterior life of Casa Pedregal also means sharing the house with a continuous flow of interested visitors, but it equally provides for less activity, especially in these times: “It is like living in a temple, in a monastery. Solitude is a wonderful lesson.”

César Cervantes, cultural promoter, has deep personal roots in the neighborhood of El Pedregal; as a boy, he too scrambled over the lava (and streets) around his own nearby home. In 2013, he sold his contemporary art collection for a deepening cultural passion: Casa Pedregal. After a sensitive three-year renovation, he now lives, fully lives, with his family in one of the most iconic of all Barragán residences: “Being responsible for it, for this patrimony, is a privilege rather than an obligation… like the privilege of parenting.”

This is the emotional range of Casa Pedregal—from the unbounded joy of exuberant family life, to generously welcoming the public, to personal retreat and solitude. And this is perhaps the most over-arching of the lessons that Cervantes identifies as having learned from living in the home in the lava fields above Mexico City. Most contemporary architecture, he says, is obsessed with “creating an effect”. It is calculated, aided by the computer, and presents as an intellectual effort. “I have been thinking about how this house does not have an intellectual effort; it is the emotional effort. This house, it is all about emotions.”