James Goldstein’s Ever-Expanding World

James Goldstein unfolds his beach chair on the strip of grass that separates his newly-finished expansion from the in-construction terraces below. All around him, gardeners plant, workers excavate, contractors check plans but he remains unfazed. He kicks off his tennis shoes, and lies back, crisping in the sun. If there was ever a man acclimated to construction, it’s Goldstein. For forty years, almost half his life, he’s been surrounded by it.

In his thirties, Goldstein had been content in a Hollywood high-rise. But when he met the “love of his life,” an Afghan Hound named Natasha, he began searching for a home with room for her to ramble. As a boy growing up in Milwaukee, he’d preferred his best friend’s Frank Lloyd Wright–designed residence to his parents’ old mansion. So he knew he wanted something modern, with a pool, a view, and enough room for Natasha to stretch her paws.

Ten years earlier, in 1963, one of Wright’s protégés, John Lautner, had designed something downright futuristic for Helen and Paul Sheats: a triangular kaleidoscope of a home where everything—walls, ceilings, swimming pool—appeared to rotate around the view of Los Angeles. But since their divorce, the residence had fallen on hard times, passed through a couple hands before ending up in Goldstein’s for the reasonable sum of one hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars. “The minute I walked in, I knew this was the one,” Goldstein recalls. “Even though it was in terrible condition. It was decorated very badly. It had negatives that I wasn’t even thinking about because I saw the design. I saw the view. And there was no question in my mind, this was what I wanted.”

But the view was blocked. The Sheatses had installed a grid of mullioned windows when the house’s original air-curtain failed to keep the cold out. For seven years, Goldstein grew his business, and looked at his windows instead of through them. As soon as he could afford to, he brought Lautner back in to construct a frameless glass partition that sliced through the coffered ceiling, concrete sofa and lush landscaping. Goldstein loved the result, which dissolved distinctions between indoors and out. But now the plaster walls troubled him. Shouldn’t they be concrete? And the rock fireplace: why was it traditional? Item by item, Goldstein would bring a problem to Lautner’s attention and receive daring solutions. “He would never suggest changes to the house. He would always wait to hear from me first. Once I came up with an idea, he would give me alternative ways of implementing it, and would always let me choose the one I liked most.” Once construction started, it never ceased; Goldstein has been renovating, updating, and expanding his property ever since.

It’s impossible to understand Lautner’s masterpiece, without understanding the client for whom it was redesigned. The Sheatses were a family of five. Goldstein is a permanent bachelor, and he turned their home into the most famous bachelor pad in America by demanding that mitered-glass windows open with the push of a button, televisions descend from the ceiling, and all-glass sinks be integrated into all-glass walls. He then invited countless tours, magazines, and film shoots in to record his accomplishment. Most notoriously, The Big Lebowski presented the residence as porn mogul Jackie Treehorn’s palace. But a couple years earlier, girls got freaky on the leather sofas in Unleashed and Possessions, two actual adult films. Typecast, the home has played the pad of pimps and pornographers ever since. Snoop Dogg covered the bed in leopard print for “Let’s Get Blown,” Nelly hypnotized his Stepford Wife in “The Fix,” and G-Eazy turned the house into a harem in “Order More.”

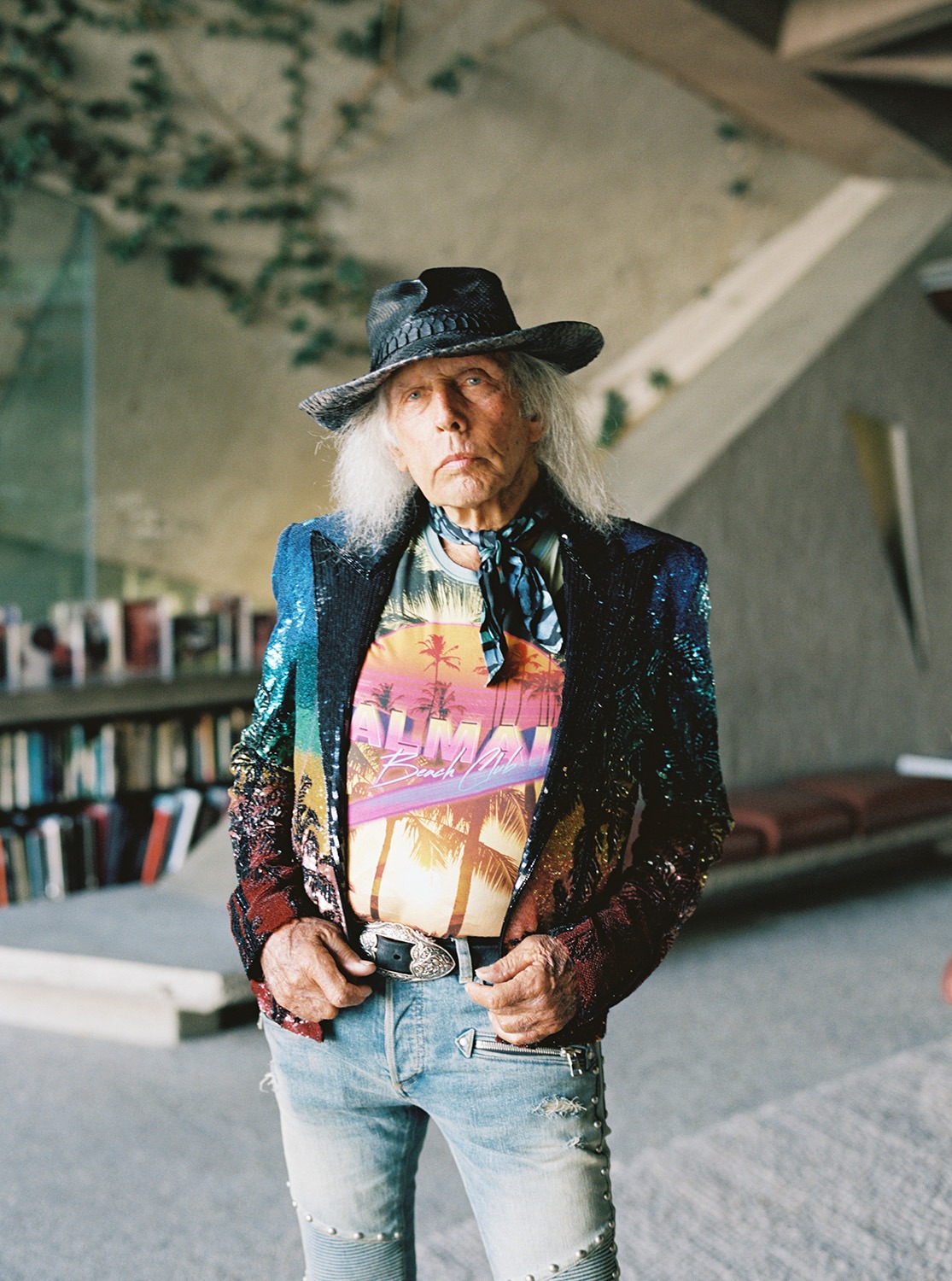

Over time, Goldstein’s public persona merged with that of his house, as he began to make cameos in the videos and redefined himself around his home’s reputation. His clothes grew wilder (Swarovski meets White Snake) and he developed a taste for arm candy (svelte and statuesque). “In my older years, I’ve become something of a celebrity,” Goldstein admits. “Thinking back to my younger days, if I had expected that sort of thing to happen, maybe I would have pushed a little more in that direction.” Despite his glam-rock Crocodile Dundee get-up, I believe Goldstein when he tells me that his newfound notoriety was “unintentional” yet gave him “a lot of satisfaction.”

In 1994, John Lautner, the genius who made this all possible, passed away. Usually our story would end there, but Goldstein felt an overriding “obligation to show this architecture to the people.” And as his house’s fame grew, more and more people wanted to see it–too many to fit them all inside. Now working with Lautner’s project architect, Duncan Nicholson, Goldstein developed three lots down the hill and turned them into tropical walking gardens with modernist follies and a hidden James Turrell Skyspace.

Goldstein also purchased Lautner’s neighboring Concannon Residence, a wood-framed house with floor-to-ceiling windows, curved clerestories, a pyramidal skylight, and cut-out eaves to capture the sun as it arced across the sky. A tenant, Andrea Kreuzhage describes her former home, “It didn’t feel like I was in a man-made structure. It was so organic that indoors and outdoors merged. Living there had so much to do with the wildlife, the birds, the bobcats, the deer that came to visit and drank from the pool.” The home’s most distinctive feature, a lens-shaped swimming pool, was carved out of an elliptical plan that overlaps like a Venn-diagram. But unlike the Sheats residence, the Concannon was “a small house, a humble house. Lautner played with the elements he found in a really unique and beautiful way, but the house was very cheaply built and it had water damage and it didn’t heat well.” It appeared to be the perfect fixer-upper for a Lautner obsessive looking to expand his property.

At the sound of my approach, Goldstein slowly opens deep-set eyes grown used to the epic view before him. At 79, It takes him awhile to climb out of the low beach chair, but once up, he volleys with his tennis partner for over thirty minutes. Even as he puts his affairs in order and prepares to donate his property to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, he is determined to stay active, live large, sit courtside at every Western Conference basketball game, and play tennis every afternoon—which is why a court now sits where the Concannon Residence once stood.

One of Lautner’s greatest champions, Goldstein nevertheless bulldozed his work to make way for the world’s only infinity-view tennis court and, buried beneath it, the eponymous Club James, a subterranean disco designed in a Lautneresque style. “The club has always been an aspiration of mine because I’m such a big clubgoer myself. And I’ve always thought about how I would design my own,” says Goldstein, who has been able to claim more creative control since Lautner’s passing. “I had been working considerably with his assistants including Duncan [Nicholson]. So that there was a natural transition. When Duncan passed away. I had also been working with his assistants [Conner & Perry] so again, there was a transition. My amount of personal involvement accelerated in each case.”

Goldstein’s dedication to expanding his property borders on mania, but a man who derives his identity from his home naturally wants to share it with the world. Where Lautner measured success by the degree to which he could integrate the individual into their environment, Goldstein appears to measure it by how many individuals he can integrate into his environment. “All-Star Weekend, over two nights we had two-thousand people here. We had twelve-hundred the first night, eight hundred the second, and the party was spread over the tennis court and the club.” Now that he’s expanding the complex to include an outdoor terrace, he boasts that if he “really wanted to push it to the max,” he could “probably have over two-thousand people here at one time.”

My first visit to the residence occurred six months earlier at just such an event: “The MAK Games,” a tennis tournament, party, and fundraiser for the MAK Center, which programs art and architectural interventions at Rudolph Schindler’s poured-concrete home, a precursor to Lautner’s experiments in the medium. The chattering classes were happy to give to such a worthwhile cause but disappointed to find that it only bought them access to the new entertainment complex.

Architect Tyler Polich describes the disco as “brutal techno chic.” Artist Esteban Schimpf sums it up drolly, “the club is very club-like,” which is noteworthy considering that it is modeled after a house that is anything but “house-like.” Where Lautner strained against conventions, his protégés accept them by wrapping lounge seating around an intimidatingly open dance floor. All the edges are chamfered to give them a Lautner look but the actual plan is still the basic box. Lautner’s protégés mistake his style for his art, flattening it into pastiche. Lautner was indeed stylish, but he wasn’t a stylist; he was a strategist who solved site-specific problems with audacious solutions.

Lautner’s work was primarily concerned with liberating us from structure and connecting us to the landscape. If he had designed a hillside dance club, the layout would have encouraged dancing—not just inside the building, but somehow beyond it, out into the view itself. Club James achieves the opposite effect, trapping us in an enclosed bunker. Here, in a concrete bomb shelter, house music echoes infernally, and the city below appears ready to catch fire. Since it isn’t possible to hear a word over a concrete club’s din, nor is it polite to talk during a tennis match, most MAK guests spent their time chatting in the non-descript drive, while waiting for their ten-minute tour of the original masterpiece.

From the carport, you can barely tell that you’re standing outside one of the most significant homes in America. The house is tucked into the mountain and turns its back on the street. As you enter, Lautner forces you down a narrow corridor, which introduces you to the hourglass interior at its most constricted point, the fireplace. From here, glimpsing the expansive spaces beyond, most guests immediately rush into the living room and then—as though propelled—past the pool to the very edge of the property, where at a martini-glass angle, concrete meets sky.

Only when they’ve reached the edge, do folks turn around and, for the first time, actually see the Sheats-Goldstein from the outside. This is the image featured in countless photos and films. The house’s most prominent feature, the triangularly-coffered roof juts upwards and leaves shimmering fragments reflected in the pool below. A similar ceiling was employed by Louis Kahn at Yale but Lautner sets his jauntily askew and pierces it with 750 drinking-glass skylights, making the monumental feel utterly weightless.

In elevation, the residence resembles a drawn bow. The roof is pulled back taut like a bowstring while the lower story juts out over the city like an arrow rest. The furthest point, the master bedroom, culminates in an angled sight window, pointing directly at Palos Verdes and the Pacific beyond. Here, you can feel the house holding you in a state of elastic tension. Press a button and the glass walls slide away, nothing preventing you from diving into ecstatic oblivion.

As I walked through the house for the first time that night, I was introduced to its owner obliquely via staggered rows of Lucite frames displaying pictures of Goldstein standing in the shadows of leggy models, celebrities, and sports stars. I followed them into his master bedroom where Natasha’s photo sits close to his bed. James Goldstein bought this home to give a little leg room to a growing pup, then opened it further and further, first to architecture students, then to fashion models, movies, and events. When he someday ascends to that great big disco in the sky, his house will be donated to LACMA, which is his way of opening it to you. All of you.

Where Lautner had originally designed a family home, and then transformed it into the ultimate bachelor pad, Goldstein now seeks to expand his residence into a public showplace: an event space, film set, nightclub, well-known spectacle, and eventually a museum object. But to do so, he’s had to seize authorial control from the architect he so admires. “With Lautner, even though he’d always allow me to make suggestions, his assistants and I were somewhat beholden to him. That’s all changed now, so that I have the final say.”